Preliminary Conclusions 17, Al Ravitz

6 Artists

On view: September 8 - October 11, 2024

1) My favorite book about art is Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees (by Lawrence Weschler, about Robert Irwin).

2) I was recently in Amsterdam and explored a room constructed by Stanley Brouwn.

3) I'm not crazy about looking at art. I like being with it, noticing how its presence makes itself felt – through material or conceptual means.

The works in this show rearrange physical/perceptual space in such a fashion as to evoke various person-specific sensory-cognitive experiences. Each artist modifies and abstracts (or vice versa) a real “thing;” which allows us – motivates us if we are open to such motivation – to reconceptualize what that “thing” really is.

These are, then, phenomenological exercises:

Japeth Mennes takes a utilitarian object, a simple produce crate, and represents it as a manifestation of psycho-spatial properties that each of us experiences differently. (For me, it’s comforting to experience this deep complexity of the world.)

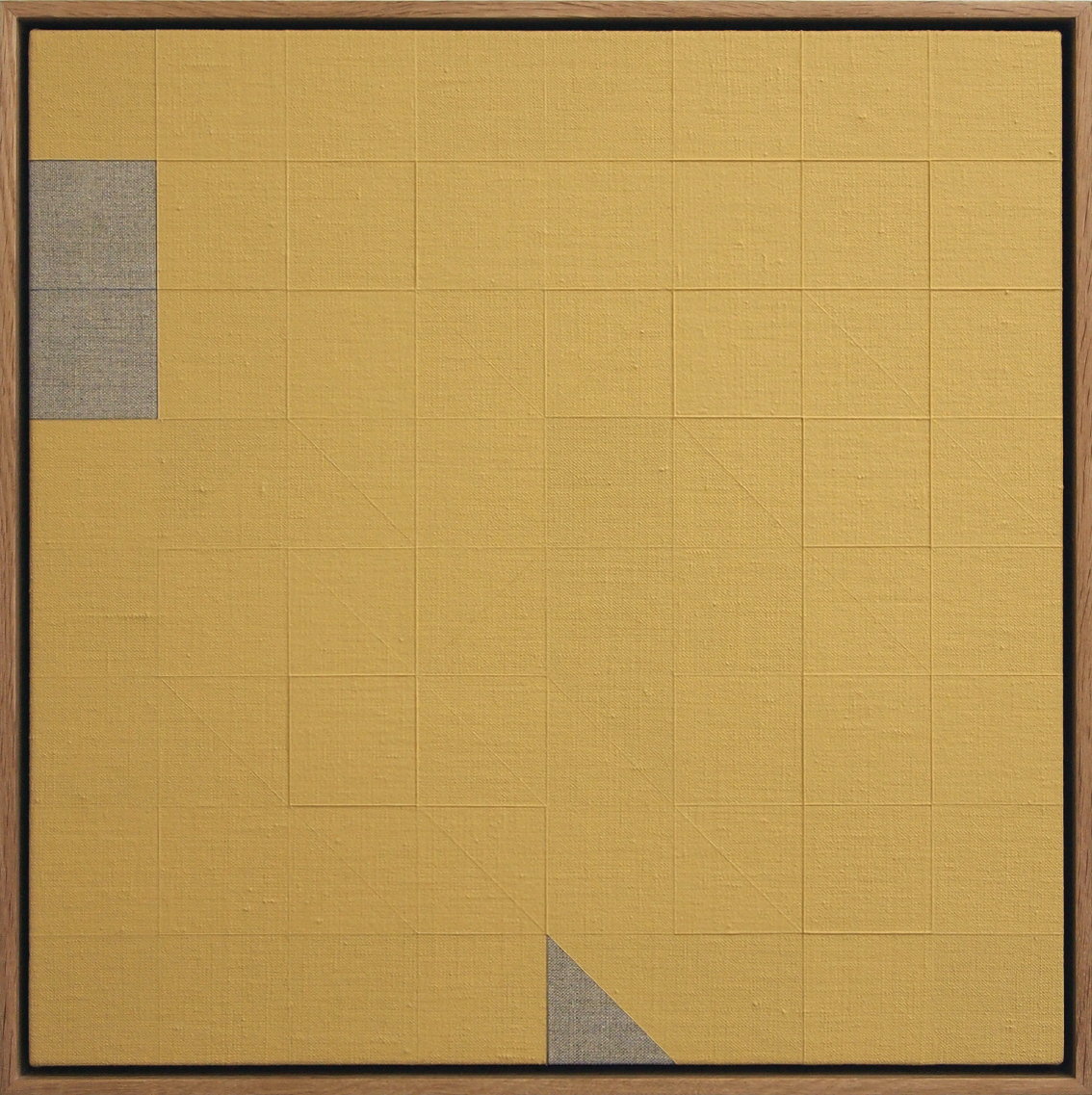

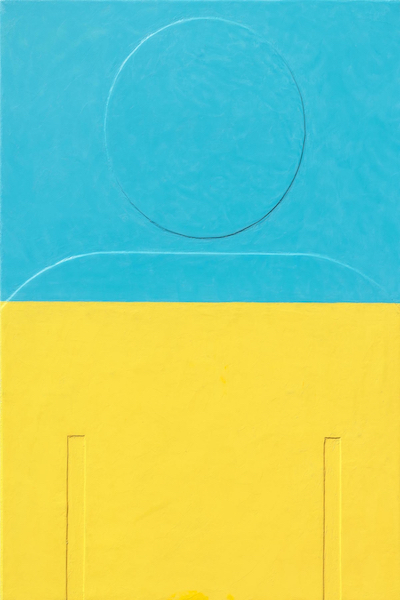

Cary Smith abstracts the concept (not the look) that underlies a well-known and powerful set of “things.” His paintings are material manifestations of an idea.

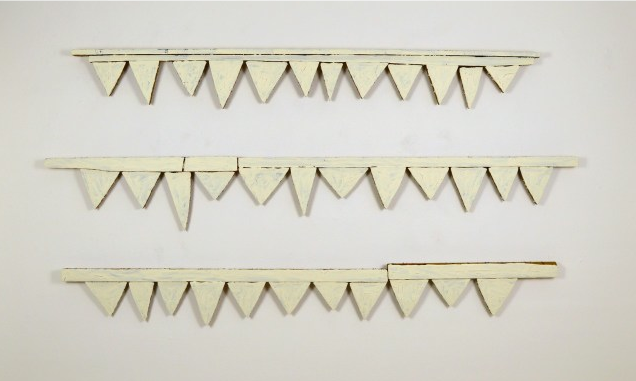

Kees van de Wal takes a “thing” to which we attribute no value – cardboard detritus – and makes it compelling by modifying its shape and color; which allows us to experience it in a different psychological context. And that experience, again, makes the world deeper and more significant.

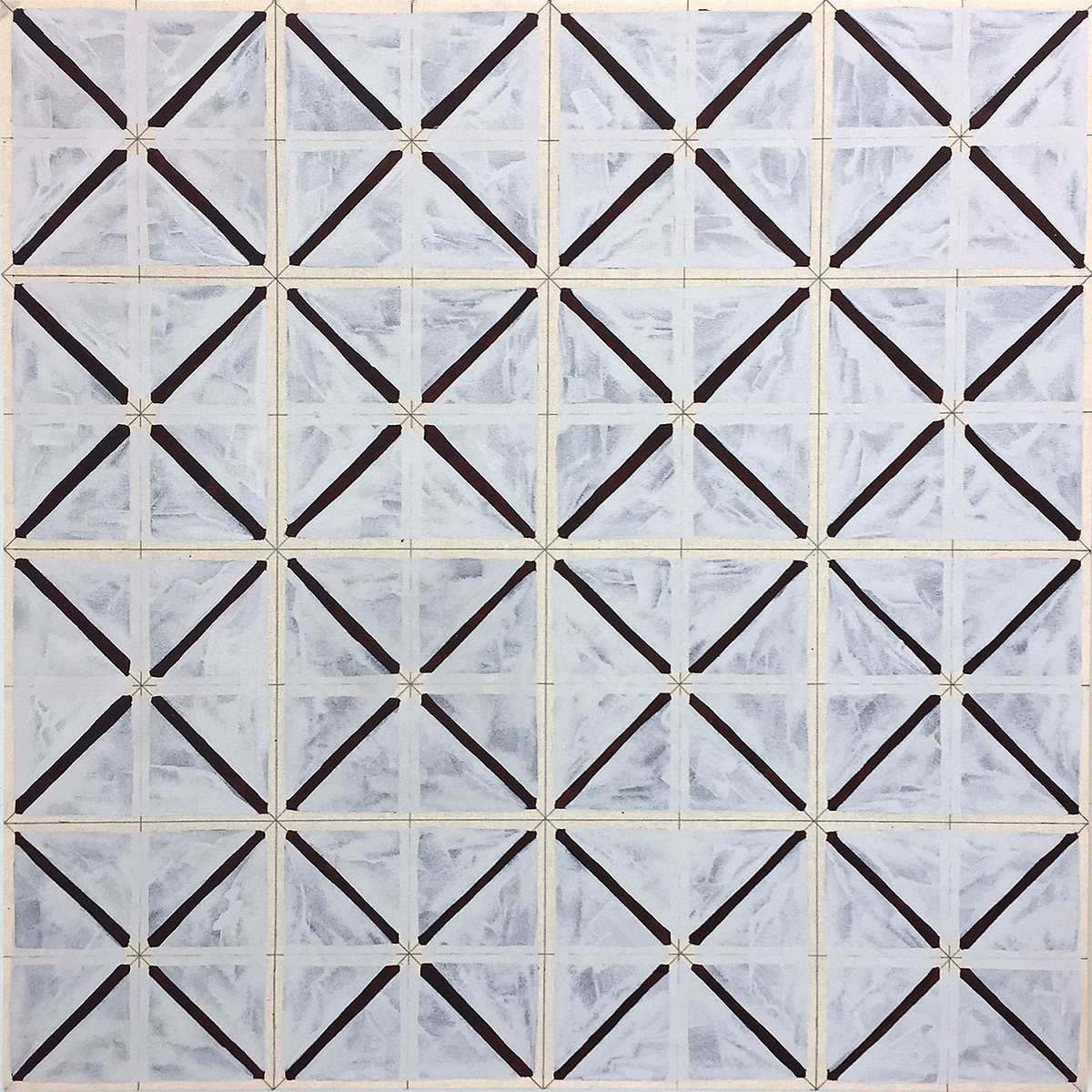

For Jacqy DuVal, the “thing” is a painting. The artists use ancient techniques in the service of creating tiny geometrically abstract paintings encased in thick plexiglas. This one requires no further explanation; just go with the flow.

Lynn Harlow endeavors to discover the real thing that underlies the “thing” we see. She strips away layers until all that is left is what is essential.

... and Thomas’s chairs? When we sit on them, they allow us to be one of the things in the show.

September 2024 exhibitions

Preliminary Conclusions 16, Al Ravitz

EYAL DANIELI- Preoccupied

On view: November 12, 2023 - January 5, 2024

There are certain intrinsic aspects of seeing; they resist classification. That’s what interests me. I try to restrict the data to which I attend, which allows me to experience a unique, as-yet-unclassified world. I’ve wanted an experience devoid of and/or all meta about narrative, but I’ve always known that those intrinsic aspects of seeing could be modified by experience. In his paper, “The Dawn Of Awareness,”¹ Gerald Stechler wrote that "awareness comes into being when some of the monitoring functions which are a necessary and universal aspect of life are transformed to a higher level of organization."

Sue and I met Eyal at an opening for a group show in Brooklyn. He was grilling meat with his buddy, Guy Corriero, who’d curated the show with Glenn Goldberg. I said hi to Guy and described a painting that was our favorite in the show. Guy said his grill partner, Eyal, was the artist. That's how we met. After that meeting, Sue probably tracked him down on Instagram and asked if he wanted to put something in a group show of small work she was curating. He gave us one of his exquisite paintings, and he spent some time in the space over the run of the show. He was a great guy. Sue and Eyal talked about doing a show in the gallery. Within a couple weeks, Eyal died. Guy reached out to tell Sue about his death. She suggested doing a memorial show, curated by Guy and Eyal’s wife, Amanda.

Preoccupied exhibition, Waiting Room installation, Nov 12, 2023 - Jan 5, 2024

Because I knew I wouldn’t be able to talk with Eyal, I read some catalogue essays and watched an artist’s talk that he gave in 2022 – things I only occasionally do – in which he discussed the deeply felt emotional experience that informs all of his work (http://eyaldanieli.com). Now, when I look at the show, I experience it emotionally. The paintings feel like solid objects, the stripes very heavy, the smoke almost ethereal, but with an emanation into the ether that evokes a pregnant sensation in my chest, one that I’ve previously associated with affect rather than perception.

Some Restrictions May Apply, 026 and 043 in Melanie’s Office during the Preoccupied exhibition

Eyal Danieli in his Williamsburg studio around 2021, photo by Ben Fievet

In the studio at work on Aura. On the table are proofs for the catalogue for Some Very Fine People, 2019.

¹ Gerald Stechler Ph.D. (1982) The dawn of awareness, Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 1:4, 503-532, DOI: 10.1080/07351698209533419

Preliminary Conclusions 15, Al Ravitz

CELESTE FICHTER - Found Found

On view: February 3 - March 11, 2022

In the effort to manage our lives efficiently, we develop a set of average expectable experience (AEE) templates, which are based on the assumption that a given set of circumstances is likely to turn out in a certain, predictable way. These AAE templates represent a weighted average of past experiences categorized according to the qualities we find most adaptively valuable; the templates generate models of what we can reasonably expect when we confront various perceptual and/or emotional and/or interpersonal stimuli.

Although there are several factors that engender experiential constancy – genetics, familial characteristics, socio/economic circumstances, larger cultural forces – luck also plays a huge role in most of our lives. To be maximally adaptive, then, we need to accurately see things. When circumstances change, we need to modify our AEE templates. Unfortunately, that doesn’t always happen. We ignore the new data, get stuck, and end up making the same mistakes over and over. What you see isn’t always what you get.

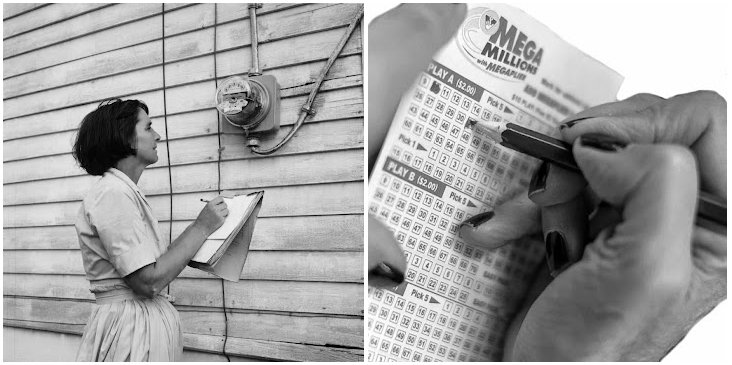

MegaMillions, 2020. Adhesive Polyester Fabric mounted on MDF. 8 x 8 x 0.75 inches.

One focus of my clinical practice is divorce. I’ve seen well over a thousand divorcing families in the last 40 or so years. Guess what? Second marriages are more likely to end in divorce than first; third more likely than second. Talk about making the same mistakes!

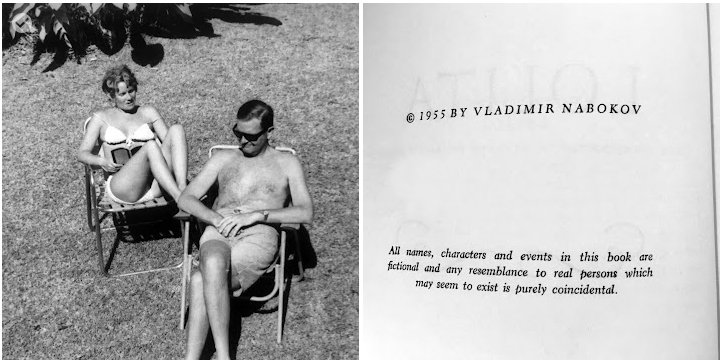

Lolita, 2020. Adhesive Polyester Fabric mounted on MDF. 8 x 8 x 0.75 inches.

Why does this happen, when it seems to make so little adaptive sense? One explanation relies on the concept of Person-Environment Transactions¹. We’re not passive observers of our lives; rather, we play an active role in creating our social, emotional, and intellectual environments. We choose to associate with people who reinforce our existing predispositions (proactive transactions); we tend to pay attention only to the data we expect to perceive, and we ignore that which doesn’t fit (reactive transactions); and often, if we don’t see what we expect, we behave in a fashion that evokes the response we anticipate (evocative transactions).

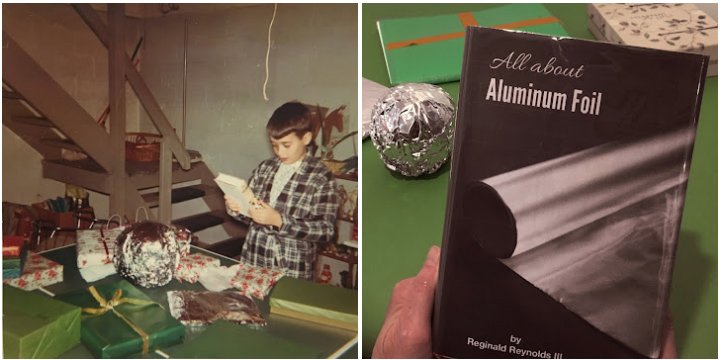

Aluminum Foil, 2020. Adhesive Polyester Fabric mounted on MDF. 8 x 8 x 0.75 inches.

In her recent show, Found Found, at 57w57Arts, Celeste Fichter presents a series of sculptural objects, double-sided panels that hang perpendicularly from the wall. On one side is a vernacular photograph, a vintage snapshot of people doing average expectable things – reading, writing, drawing, kissing – and on the other is an image of something unexpected. The paired photo clearly relates to the initial perceptual stimulus, but only in retrospect, and only if we allow ourselves to see what we hadn’t expected to see. It’s an intervention, then, at the level of reactive person-environment transactions. Celeste tells us to look carefully before assuming we know what’s going on. The work forces us to recognize that our tendency to organize perceptual data in the service of supporting predispositions prevents us, at least sometimes, from seeing what is really there.

Just Married, 2020. Adhesive Polyester Fabric mounted on MDF. 8 x 8 x 0.75 inches.

The work may be funny, but it also teaches us there is another way of seeing the world.

Celeste Fichter, Found Found at Project Space Installation view (Photo by Luis Corzo)

¹ Caspi, A., & Roberts, B. W. (1999). Personality continuity and change across the life course. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (Vol. 2, pp. 300–326). New York: Guilford Press.

Preliminary Conclusions 14, Al Ravitz

LOT-EK & RUCKERCORP

On view: March 5 - April 16, 2020

Chris Rucker’s exhibit in The Project Space, a sculpture and series of densely hung paintings, reminds me Gerhard Richter’s Six Gray Mirrors (2003) at Dia. When you walk into that room there’s so much there that you can’t really “see” it. The best you can do is to recognize that each time you’re there, it's different. You have to be with this work to really look at it. Marcia Hafif, who primarily painted monochromes, used to always tell me that she was at least as interested in the relationship of each painting to all the others as she was in the individual paintings themselves. This, I think, is another way of incorporating context and memory into perceptual experience.

Ruckercorp, Project Space Installation View

Chris’s show also reminds me – in the best possible way – of watching construction. If you just look at it once or twice, depending on the interval of time that passes, you’ll see either no change or a total transformation, but if you look at it every day, you see the process of transformation. I’ll add that because of Covid-19, I’m in the country every day, intimately experiencing the green life that surrounds me. Each new day everything is the same and different, like one of Marcia’s paintings or a Ron Cooper light trap under changing light conditions.

Ruckercorp, Project Space Installation View (detail)

That's what happens with these paintings. They’re hung so densely that you're just surrounded by them, like those gray mirror paintings at Dia. You can't get far enough away to see the whole thing; it’s atypical data, so it’s difficult to incorporate into already existing perceptual anticipatory algorithms. You have to be in the room – to experience the way the sculpture forces you to deal with it – to really see this show. Then, once you’ve incorporated the memory, the show will accompany you.

STACK/ROTATE END90. 2019. Laser-cut upcycled (3) cardboard boxes, flattened and sprayed with acrylic. 20”x 74” cardboard, overall dimensions variable.

LOT-EK’s show is, in certain ways, more consciously conceptual than Chris’s. It is the more overtly "intellectual" experience. In their work, Ada and Giuseppe utilize containers that surround empty space, and then they place those containers in relation to each other. The drawings on the wall of The Waiting Room not only represent those empty containers in relationship to each other, but the corrugated nature of the support and surface of the work itself interacts with the empty space in the room in such a way as to reify the idea of structures containing space.

LOT-EK has chosen to utilize a kind of anti-aesthetic object as the basis of their aesthetic system. It speaks to the idea of context, and the meaning that we attribute to things based on their context. The meaning of shipping containers is different than it used to be because of LOT-EK. These wall pieces reflect LOT-EK’s creation of a new aesthetic system with a unique set of values.

To summarize, we develop (anticipatory) models to quickly categorize and adaptively master a wide variety of experience, including a specific type of perceptual/emotional/cognitive experience referred to as (psycho)aesthetic. We add more or less data to this model every day. Consequently, each instance of our taking the time to carefully see the same thing (or some close variant) leads to a more nuanced and therefore richer perceptual experience. The point of both of these shows, then, is that they simultaneously engage the left (verbal/conceptual) and right (emotional/experiential) sides of the brain. This interaction – as I’ve noted possibly ad nauseum in other Preliminary Conclusions – deepens our (psycho)aesthetic experience.

URBANSCAN BLOCKS. 2016. Laser printed black ink on yellow pads with string and Plexiglas. 50 selected images from 56 categories of the Urbanscan series printed recto on 50 sheets. One image visible. Sheet dimensions: 8 1/2x 14”. Image dimensions: 7 3/4x 7 3/4”.

(Photographs by Riley Spencer, 2020.)

Preliminary Conclusions 13, Al Ravitz

GARY GISSLER - Neural Distillation

JESSE HICKMAN - Rowing the Boat

On view: January 9 - February 20, 2019

My experience of art is almost entirely nonverbal, so writing about it is always a struggle. I’ve discussed psychoaesthetic experience in the past. I've said that it has to do with the way objects in a space influence the experience of people who inhabit the space. Thinking about Gary Gissler's work has stimulated me to try to put some of these ideas into words.

Earlier, Michelle Alpern showed in the Project Space. Here’s what I wrote then:

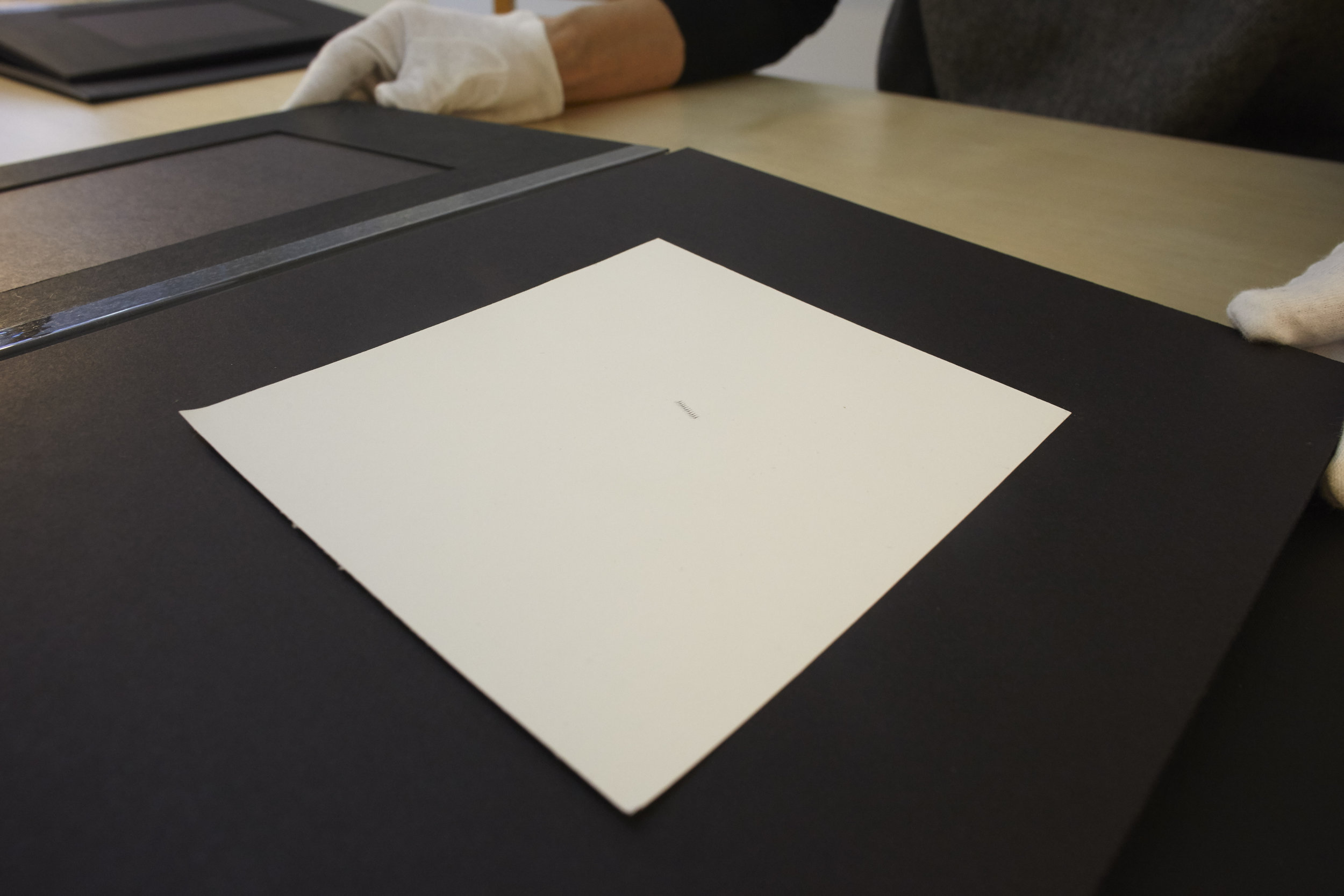

The Michelle Alpern drawings in our Project Space reside within a very specific environment – mounted in books on a table, lit with specific table lamps, you have to wear gloves to turn the pages. It’s hard work. The images are tiny – tiny – so small you don't want to bother to look at them because you assume there will be nothing there to engage your interest. It just looks indecipherable. You have to force yourself to sit and open (or empty) your mind, so you can inhabit the invisible world. After some effort the images expand until you can see something, but what you see turns out to be indecipherable, a language without symbols or narrative content. It’s an itch you can’t scratch, so you just have to get used to it. The process is liberating; it frees you to see things in an entirely new light.

Gary Gissler, We Are Dying to Give, 2019

Gary's work has something common with Michelle’s. It’s entirely abstract, but there’s a familiar pattern out there, a kind of organizing principle – words in a book I’ve read in the past – from which I have to free myself in order to see what’s there. Which is on the one hand, entirely illegible, and on the other, deeply evocative, at least in small part because it reactivates a pattern of neural firing somewhere in my brain.

Gary Gissler, Neural Distillation, Project Space Installation View

We generate cognitive/emotional templates so that we don't have to spend that much energy interpreting our experience. Work like Gary’s challenges that tendency. It stimulates us to modify the assumptions we make about the way things will be. There are words – you can see that’s what they are – but you can't read them. Even when the letters are legible, they're indecipherable. The left brain ambivalently defers to the right, to their mutual benefit.

Jesse Hickman, Is Isn’t Was Wasn’t, Detail

As for Jesse Hickman, his work reinforces this feeling that there is an invisible structure that predicates how things fit together in the world. I recently read Calvin Tompkins’s New Yorker article about Buckminster Fuller. He was interested in the same sort of thing; he talked about the energy content of various arrangements of things.

Jesse’s drawings and sculpture just fit; they are coarsely material and elegant at the same time. Place them in a space and they gently alter the ether, and somewhere in the middle of the room all the waves converge, and etc.

The work blends into the underlying structure, evoking a neuropsychological response affirming that things, at a very basic level, are both invisible and consistent.

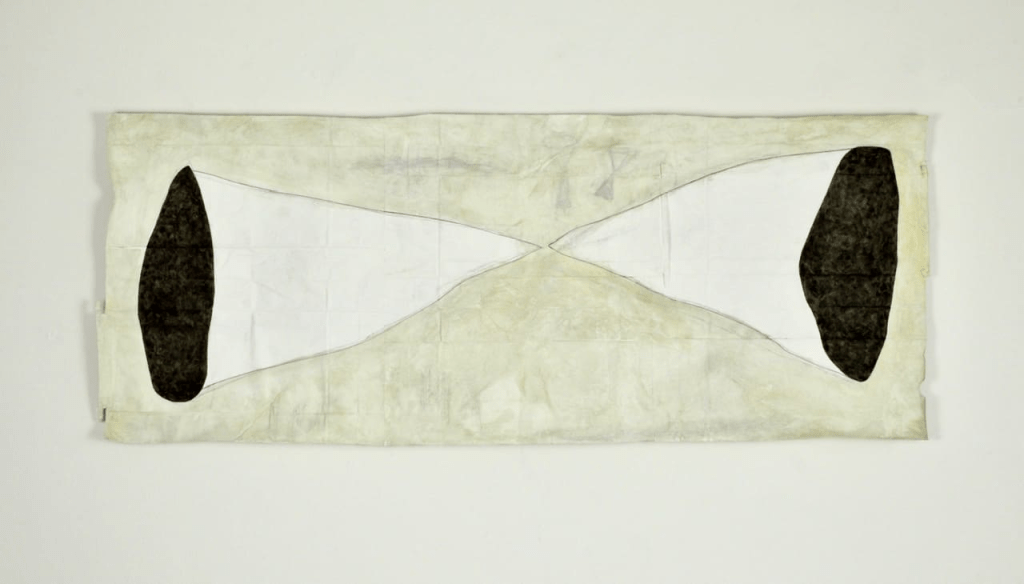

Jesse Hickman, Rowing the Boat, Waiting Room Installation View

Preliminary Conclusions 12, Al Ravitz

STEVE RIEDELL - Falling / Rising

ADRIAN WALD - Clamp Crushed, Paint Smothered

LYNN LELAND - Paintings From the 1960s

On view: November 1 - December 20, 2019

It’s 01/01/2020, the beginning of a new millennium. Sue, Tito, and I took a long walk in the country this morning. I spent this time looking and remembering. It occurred to me (other things also occurred to me) that I’d been reading a lot of “most important artists, art, etc. of the last year, last decade, etc.” (I subscribe to a lot art-related email newsletters.) My general – although not exclusive – response to what I read was that I just couldn’t relate. Much of the work (not Hilma af Klint’s) struck me as didactic, resistant to idiosyncratic interpretation – work that “means” something. I’m not interested in art that tells me what or how to think. Rather, I want a noncategorical, inarticulate experience, something to add to my invisible world algorithm. (I’ve addressed the invisible world concept in previous essays.)

As I continued to walk, I had two thoughts: First, I want being with art to be like taking a very mild psychedelic. I want to focus in, not out. I want to have an experience I couldn’t have anticipated, because I’ve never had it before. Second, I just read Gary Indiana’s Depraved Indifference, which more or less conveyed the same message as most of the “most important art of 2019” list, but it was less didactic, way more fun, and totally, creepily prescient.

Sue is rereading a biography of Alfred Barr Jr. She pointed out the following passage:

“Barr frequently justified his austere taste in art with his favorite quotation: ‘Art teaches us not to love, through false pride and ignorance, exclusively that which resembles us. It teaches us rather to love, by a great effort of intelligence and sensibility, that which is different from us.’“

From Alice Goldfarb Marquis’s Alfred Barr, Jr.: Missionary for the Modern

I haven’t written one of these Preliminary Conclusions in a while. I think I probably stopped because the whole 57W57ARTS enterprise seemed overwhelming. Sue and I gave up the large space, which included the Main Gallery and Back Room. We thought of just closing, but eventually figured out a new, lower cost strategy. In the meantime, the hiatus gave me an excuse to stop writing. It’s really hard for me to verbalize my peculiar nonverbal experience; and to further complicate the writing process, I always have much too much to say, so I get sidetracked into tangents and can’t finish anything.

57W57 Arts, Lynn Leland and Steve Riedell, Installation Views

Regarding 57W57, Sue and I eventually decided to mount shows in three or four distinct spaces, and to curate my office. Melanie sees patients in Melanie’s Office; people wait for Melanie, Mike, and me In the Waiting Room; the Project Space is an empty white cube, usually with a chair in the middle, and my office is my professional office, where I see patients, review documents, and write reports. We try to fill these spaces with things (including the work on show) that evoke a distinct, personal, noncategorical experience. All of the spaces relate to each other.

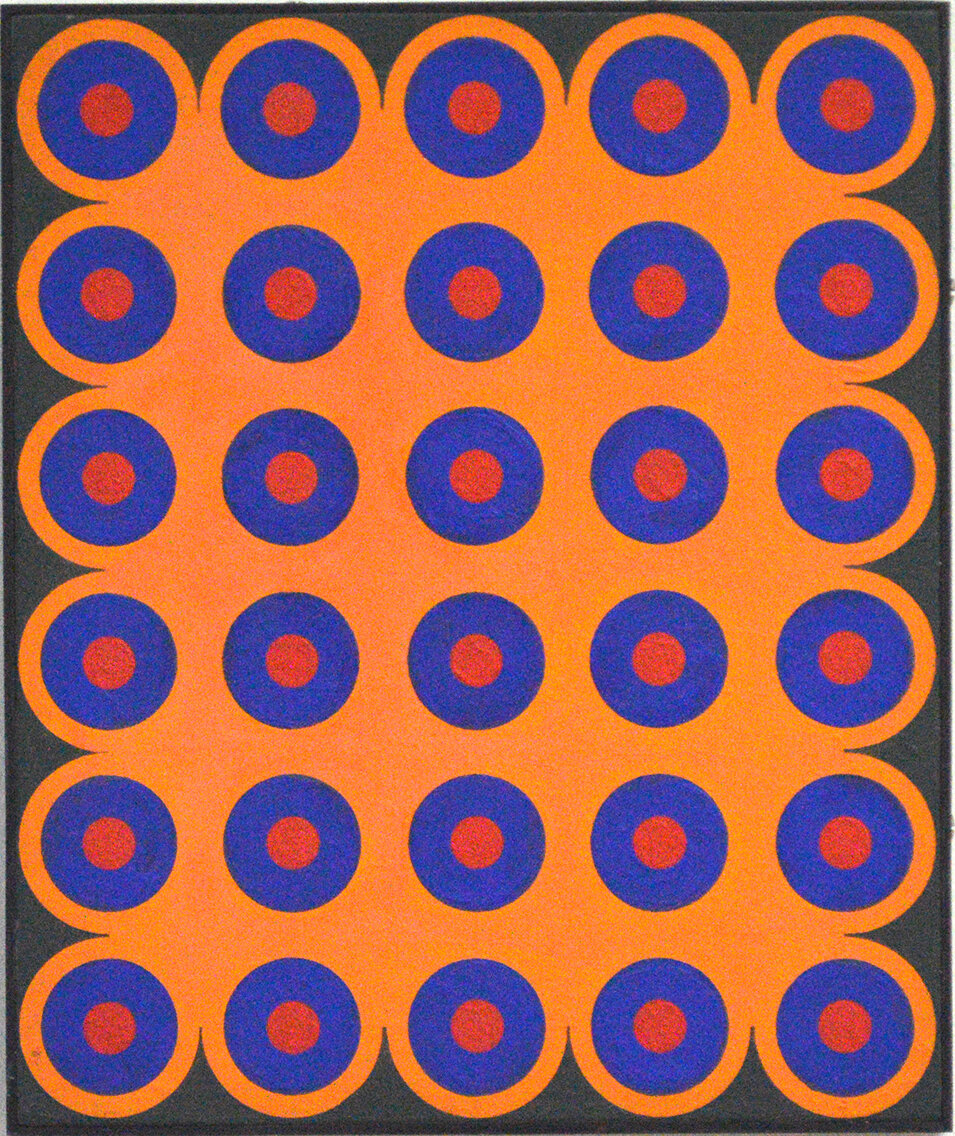

For the current shows, Melanie’s Office is hung with Lynn Leland paintings from the 60s. Some are based on music; others have numerical titles; all have lush surfaces under which the viewer can see the pencil marks that serve as an organizing grid for Leland’s little circles.

Lynn Leland, Paintings from the 1960s, Melanie’s Office Installation View

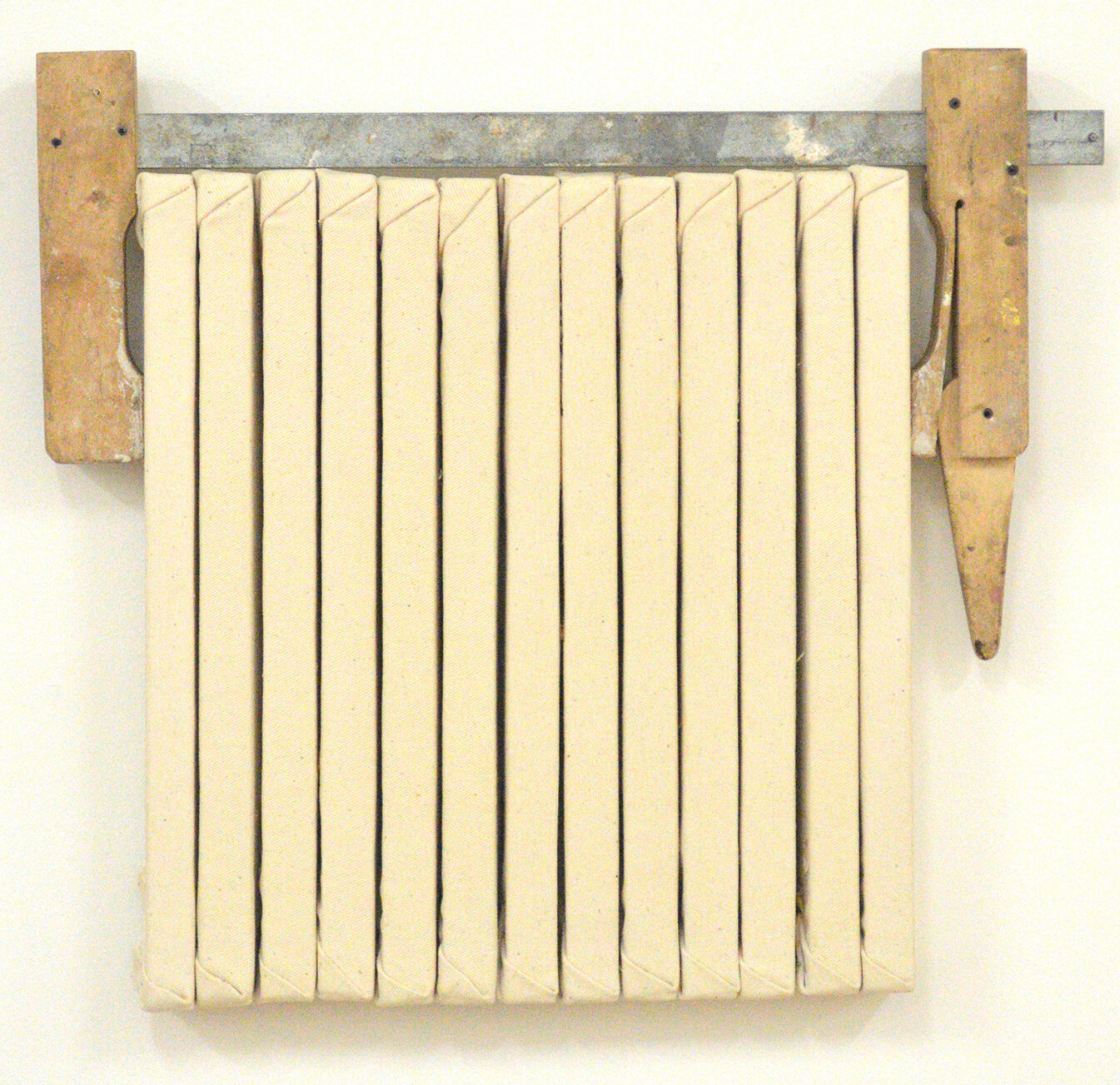

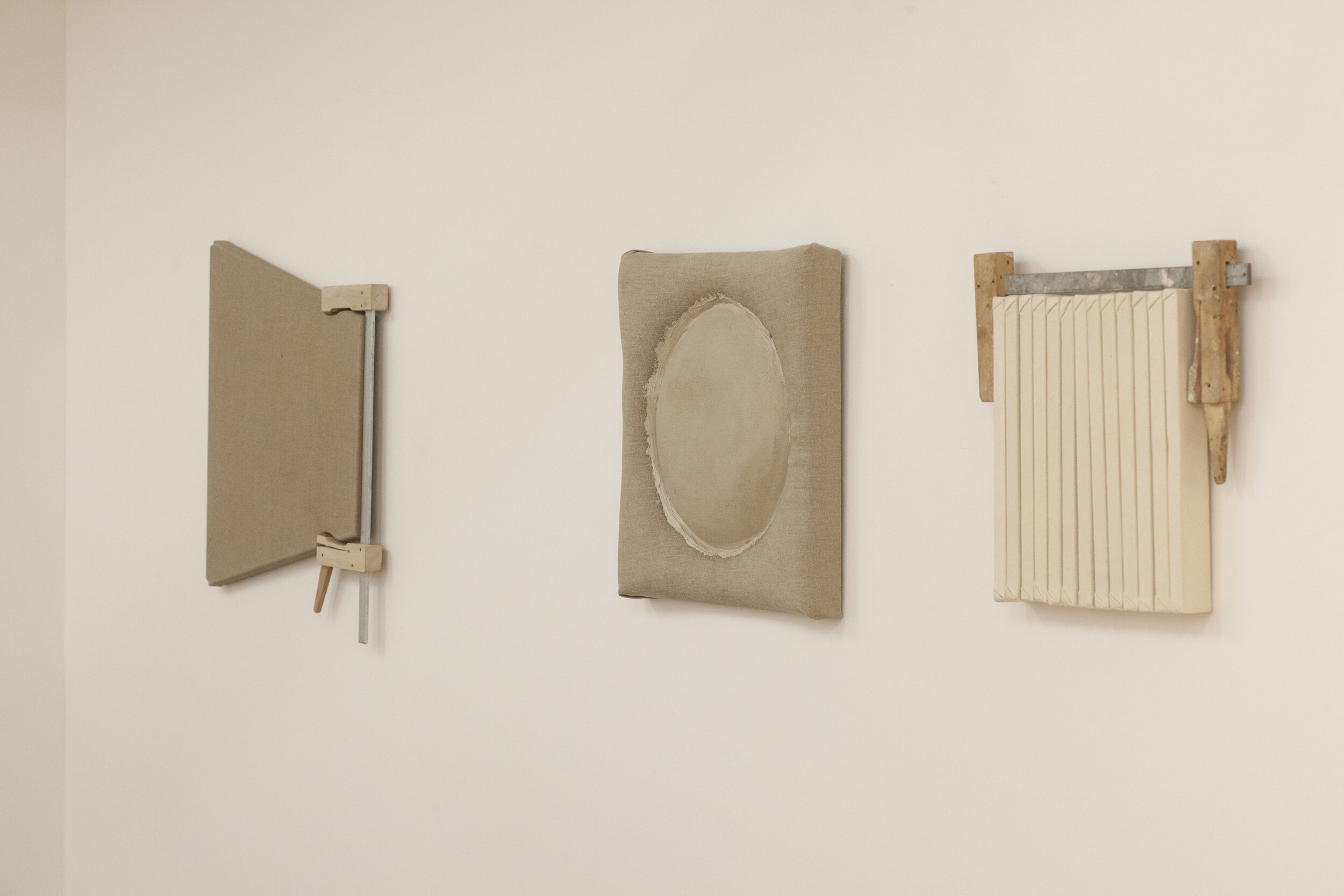

Adrian Wald’s constructions are in the Waiting Room. They utilize an arrangement of raw canvas and carpenter’s materials. These things by themselves are relatively quotidian, but in relation to each other they become otherworldly. I like otherworldliness. It opens me up to the possibility that things really are invisible.

Adrian Wald, Clamp Crushed, Paint Smothered, Waiting Room Installation View

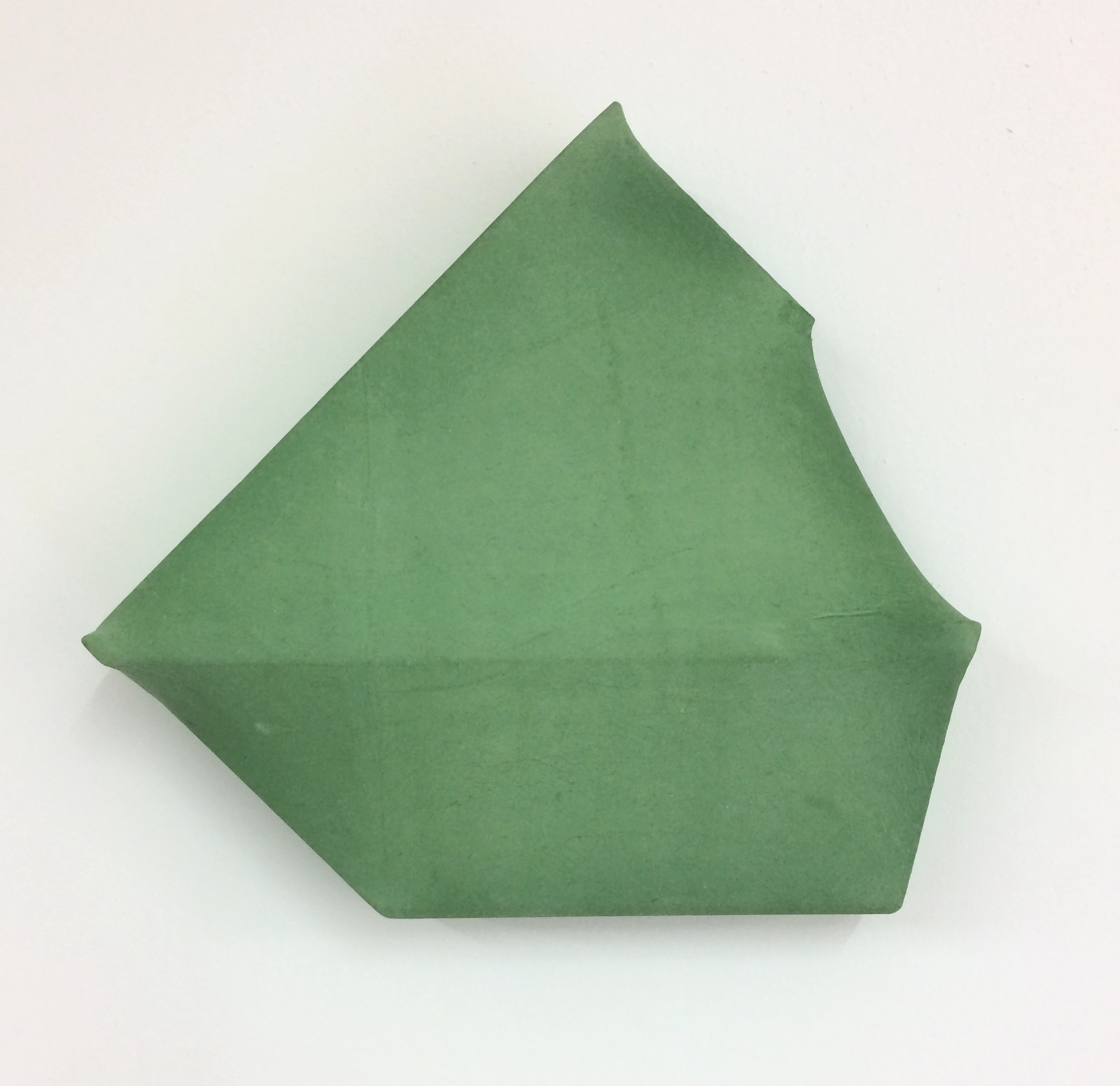

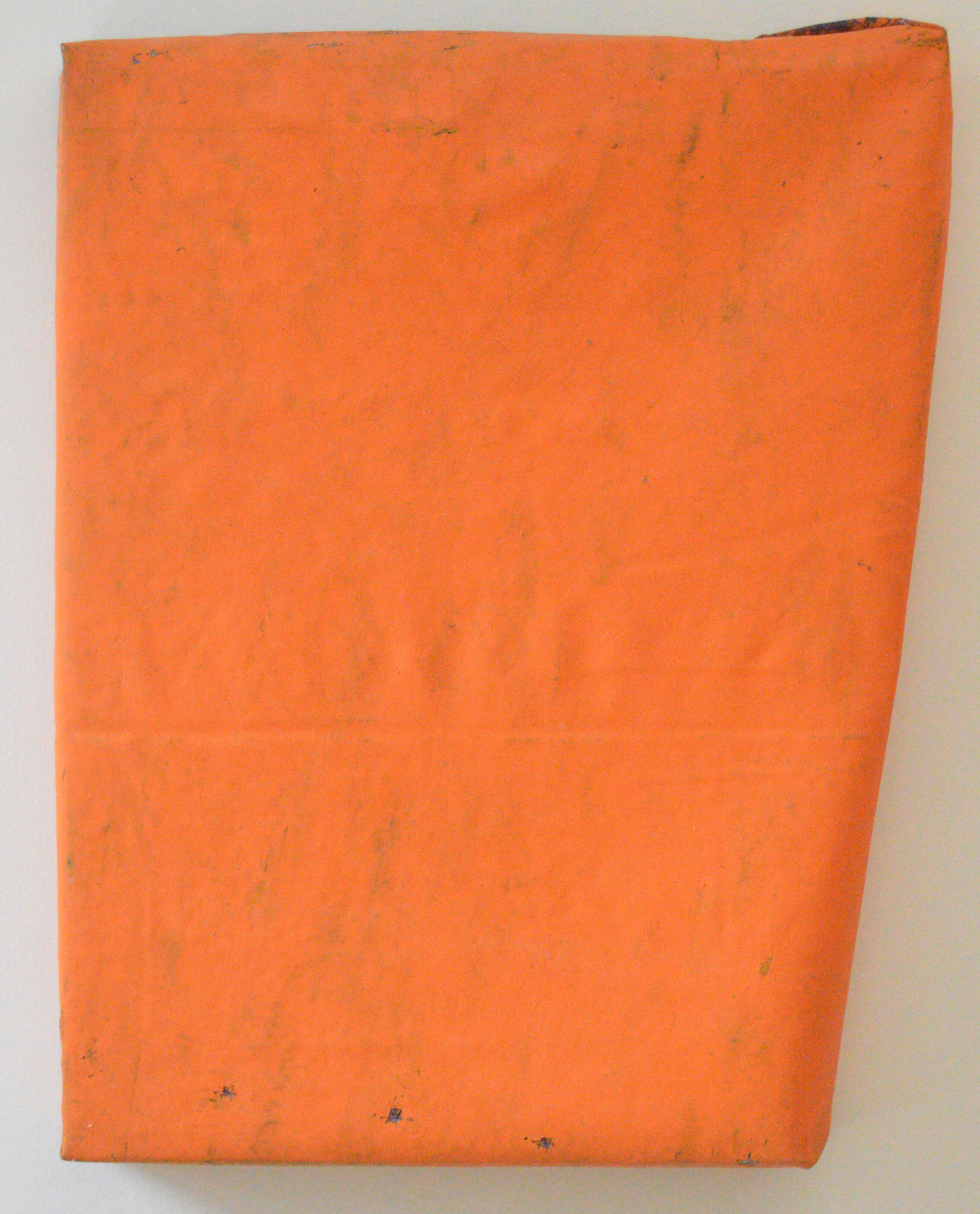

Steve Riedell’s folded paintings are in the Project Space. They’re sculptural, but they occupy space as paintings, not objects. (Don’t ask me why.) The surfaces at first appear monochromatic, but upon closer examination they are heavily worked, such that every time I look at them, I see something different. Also, the not-flat surface interacts with the changing quality of light such that no two views of a given piece are ever – my grandson would say “never ever” – the same.

Steve Riedell, Falling / Rising, Project Space Installation View

Preliminary Conclusions 11, Al Ravitz

HERMINE FORD - 8 Paintings, 2 Drawings, 1995-2007

HOWARD SCHWARTZBERG - Back and Forth

JANET PASSEHL - Rapt

ERIC HIMMEL - Towers

On view: May 4 - June 8, 2018

Although writing these things has never been easy for me, it's been especially hard to write this last Preliminary Conclusion, about the last show of this iteration of the gallery. These essays are short, but they take a long time to figure out. I try to find something that ties the shows together. I totally trust Sue’s curating, but she has a nonverbal brain – and my attempts to tie things together verbally is often a stretch.

I've talked about psycho-aesthetic experience in the past. It's a kind of noncategorical feeling state evoked by the placement of things in a context – neither happy nor sad, nor anything like that; more of an activation state unencumbered by a discrete emotion.

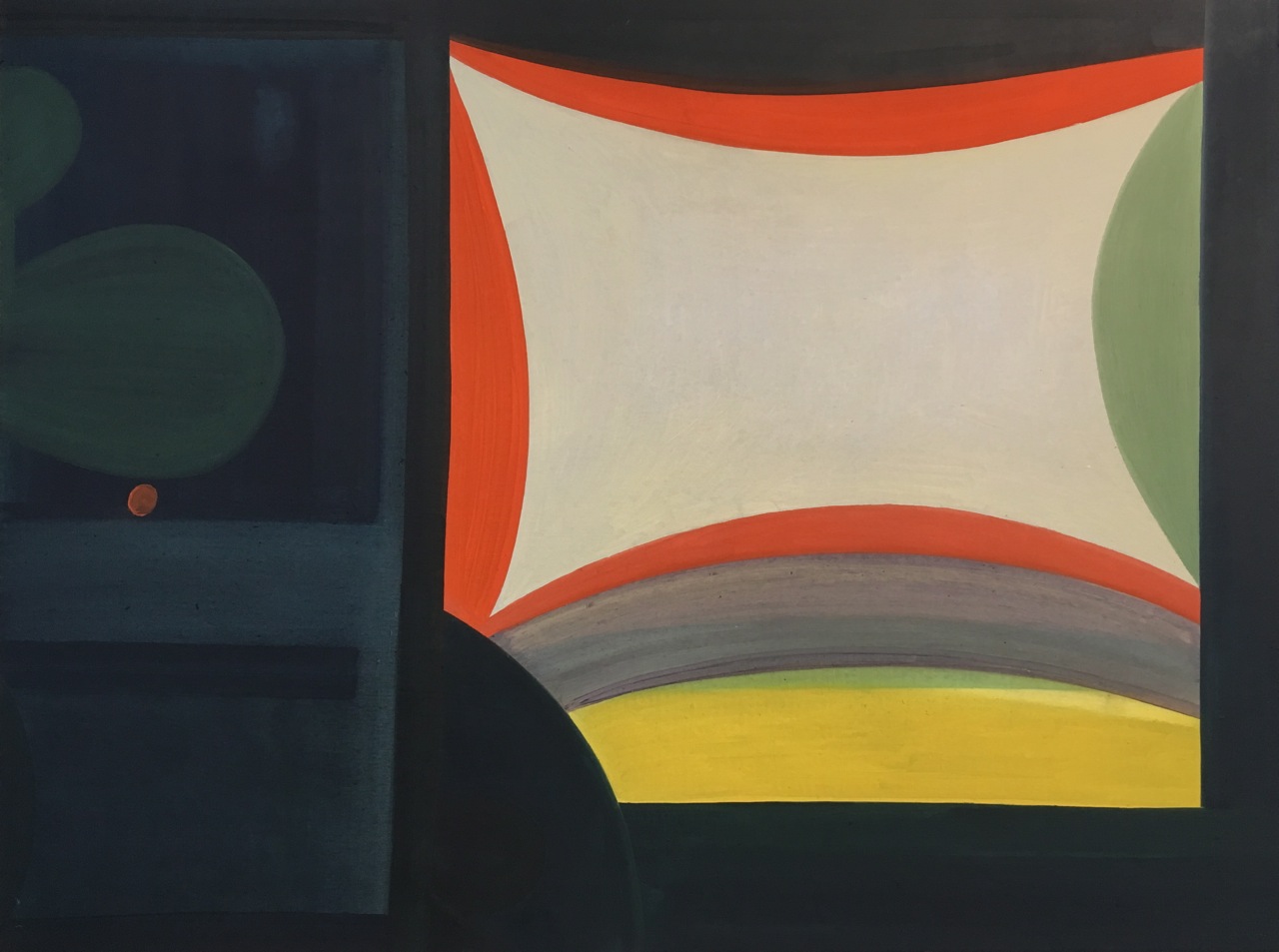

Eric Himmel's sculptures consist of flat (sometimes curved) planes that define three-dimensional spaces of varying density. These recognizable spaces generate a set of affective experiences; each feels different physically and psychologically – empty or full, light or heavy. The spaces become one thing, the sculpture. They remind me, for some totally idiosyncratic (i.e. personal) reason that I can’t figure out, of the architecture in Bertolucci’s “The Conformist.” You’ll have to take a look at the movie to see what I mean.

Eric Himmel, Towers, Back Room Installation View

Howard Schwartzberg creates spaces that are intrinsically noncategorical. There is no verbal referent. These are three dimensional things that look like paintings. The two-dimensional surface is embedded in a three-dimensional context – something flat and shiny in a rougher surround, empty disks of colored light.

Howard Schwartzberg, Waiting Room Installation View

Hermine Ford also utilizes shape to evoke an affective response. We showed work that spanned several years. It begins biomorphically and ends with hard edges (containing some softer forms, which are themselves composed of harder edges). I’ve been reading a book called Psychoanalysis and Motivational Systems. The authors write that “brain sites that are preset to respond to a particular category are activated” when we process the perception of “a stimulus that induces an emotion.” I found the softer shapes easier to look at, while the most recent painting was much harder work – but that’s a good thing.

Hermine Ford, Main Gallery Installation View

Finally, there's Janet Passehl. Her work is both flat and three-dimensional at the same time. And there's no color to distract, just monochrome to intensify this idea that the world is much more mysterious than we usually imagine. Also, it bears mention that her installation itself – the table, the sculptures on the table, the drawings on the wall surrounding everything – was just so beautiful.

Janet Passehl, Project Space Installation View

Preliminary Conclusions 10, Al Ravitz

ELISE FERGUSON - Cloudbank

JOHANNA UNZUETA - When the wind goes wrong

RICHARD ROTH - Close Call

LUIS CORZO, SUE RAVITZ, KEEGAN MILLS COOKE - Untitled (Cigarette Box) 2018

HEALEYMADE - Baba

On view: March 9 - April 20, 2018

Early on in this set of essays, I talked about being with, rather than looking at, art. I'm with art all the time when the shows are up. I don't necessarily sit in the rooms with the work, although sometimes I do, but I walk through all the rooms all the time. Sometimes I just walk in and out for a minute. Occasionally I see something I haven’t seen before; other times I have a thought and/or a memory, and I have to go back to look at something. I end up experiencing the quality of the space; how the ether is affected by the stuff in the room.

When I try to describe what I'm talking about I keep referring to an invisible world. It’s hard to define, but I think it’s composed of at least two things. First, there’s incoherence, a rejection of conventional narrative interpretation, and second, there’s cognitive rigor underlying the incoherence.

I can’t really reconcile these two points of view, except by combining them into a single thing – you know, like “something is happening but you don’t know what it is.” (I’m showing my age.) So everything I look at ends up being imbued to a greater or lesser extent by this weird single thing – which morphs recursively through memory, experience, and attention.

These are some of the thoughts I had regarding the show we just took down:

Elise Ferguson's paintings are variations on a theme. Each expression is sort of the same, but every one is different. The variations are based, I think, on certain rules that have to do with human intervention. A corollary thought I had was that these intensely evocative things were all kind of stamped out of a machine, but before and after the stamping, Elyse infused each of them with evidence of her existence. My experience of the ether (see above), then, was subtly altered every time I stepped into her room. Things just got more interesting.

Elise Ferguson, Cloudbank, Main Gallery Installation View

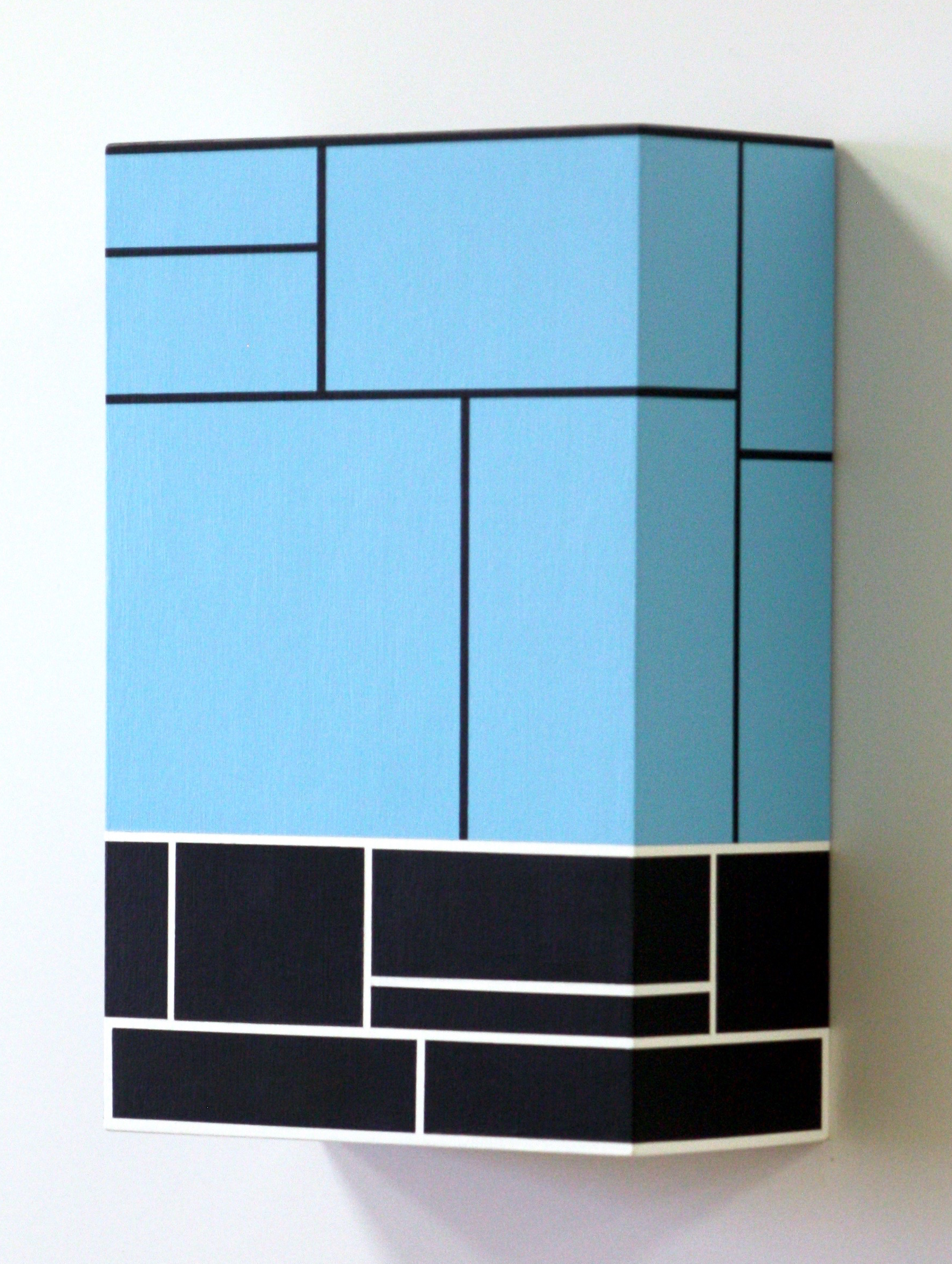

Richard Roth’s painted sculptures look perfect, even though on close examination they are obviously handmade. Each literally intrudes into space. The edges are hard, but the intrusion isn’t – similar to the Albatros chair in the little room with Richard’s work. Each piece is painted with specific attention to the three-dimensional aspects of the evoked experience. Each sculpture looks different every time I move, even though I know it’s the same. I like that thought. For an old hippie like me, it’s really deep. I also like the idea of thinking about the surface of the wall, with its various intrusions, as a thing unto itself.

Richard Roth, Close Call, Project Space Installation View

Johanna Unzueta strips utilitarian objects of their utility. She softens them as well. She turns them into abstractions, devoid of function, but the shapes nevertheless evoke sensory/affective memories that are extremely strong. You want to touch her work, which is interesting, since in the other world, the visible world, you would have no desire to physically interact with these types of objects. Thus, the instrumental is transformed into the incoherent. How sublime is that?

Johanna Unzueta, When the wind goes wrong, Waiting Room Installation View

There are two shows in the back room. Healeymade created twelve iterations of Baba, a figure from my deep childhood that I’ve never seen before. Baba evokes the feeling I get when I read Raymond Chandler – or even better, Rex Stout: this sense that things sort of fit together, but there are always complications.

Healeymade, Baba, Back Room Installation View

Finally, on the other shelves in the back room, a show curated by my wife. It's a reflection of her curatorial instincts. She likes things that are beautiful but not necessarily popular. In this case, a bunch of Italian ceramic cigarette boxes from the 50s and 60s that she bought on eBay. She also likes to engage with interesting people. Luis Corzo has always taken really great photos of the space. Keegan Mills Cooke is one of these people with an unbelievable aesthetic sense. Sue reached out and told them to just do what they wanted. She doesn't like to tell people what to do. The result was this show – her boxes, Luis’s photos, and Keegan’s book.

Luis Corzo, Sue Ravitz and Keegan Mills Cooke, Untitled (Cigarette Box) 2018, Back Room Installation View

Preliminary Conclusions 9, Al Ravitz

LOUISE BLYTON - Butterflymilk NYC

KEVIN McNAMEE-TWEED - Slow Rocket

BEVERLY RAUTENBERG - [My] FAVORITES

JOEY WATSON - Contact High: Utilitarian Objects for a Special Time and Place

On view: January 12 - February 23, 2018

This show and only two more to go before I retire to our garden in the country. I want to wrap up my thoughts. I recently had a discussion with a young artist who was very interested in digital art. I said I'd been thinking about certain art-like things for a long time, and I hadn’t finished thinking about them, so I just wasn’t that interested in thinking about other stuff.

I’m a psychiatrist. When it comes to psychological and mental health issues, I'm much more interested in the general systems aspects of things – the way everything influences (is) everything else – than conventionally valued narratives of individual experience. With art, I like the way non-verbal, non-narrative, non-valued objects interact with space to evoke an idiosyncratic psychoaesthetic/neurophysiological response.

When I slow down enough to be with the art I like, I'm regularly astounded by the impact of everything on everything else. I'm interested in:

· how material, shape, and color interact with the central nervous system;

· how information transitions from residing within an object to residing within a mind;

· how the perceptual apparatus interacts with the cognitive and affective apparatus;

· how things in a space influence the experience of that space.

As for the artists in this set of shows curated by my wife's right brain, I'll start with Beverly Rautenberg. Her work is non-narrative, but she attaches art historical antecedents to most of the pieces. I had to struggle to ignore this history in order to see them the way I wanted. There was, however, a beautiful piece called Self-Portrait of the Artist, a 1”h x 5”w x 5”d square of painted wood inserted into a corner at exactly 71 inches. I like this title. It provides a structural framework without a clear narrative. It's such a good idea. And it looks so good.

Beverly Rautenberg, [My] FAVORITES, Project Space Installation View

Louise Blyton's paintings are devoid of an easily recognizable narrative. They are just shape and color and material. Some are acrylic; some pure pigment. You can see the difference. They are all very dependent on the specific quality of light in the room. What I've been thinking about is the way they intrude into space, the specific quality of that interaction. They radiate into emptiness, and the boundary of that radiation, the degree to which it is farther from or closer to the surface of the canvas, is determined by the quality of light in the room.

Louise Blyton, Butterflymilk NYC, Main Gallery Installation View

Kevin McNamee Tweed’s monoprints required me to give up my (generally abstract/reductive) biases. I had to look at them like I was looking at one of those Magic Eye books. Kevin typically starts with a relatively conventional image. He then does something weird with it that serves both as a formal device to manipulate the space and as a way to disarticulate the image from its typical narrative context. It's mind expanding in that way. Once I divorce myself from my typical neural connections, the pictures are formally strange and emotionally evocative, but the emotion has more to do with non-categorical, quantitative affect than with discrete emotions for which there are words and clear historical associations.

Kevin McNamee-Tweed, Slow Rocket, Waiting Room Installation View

This gets me to Joey Watson. The work is sort of like a kinder, gentler, more utilitarian, definitely more psychedelic version of Hans Bellmer – with all those attendant associations. Joey's work is highly sensual, but it's not pornographic. Rather, it speaks to the deep connection between the mind and the body.

Joey Watson, Contact High: Utilitarian Objects for a Special Time and Place, Back Room Installation view

Preliminary Conclusions 8, Al Ravitz

GUY C. CORRIERO - Backward Thinking

JOHAN DECKMANN - First Editions

BRIGITTE CORNAND - Me & You

ROBERT GUILLOT - ...over and all about

On view: November 3 - December 15, 2017

I recently read a book called West of Eden: An American Place, by Jean Stein. Ed Moses, in an interview about his experience taking care of a schizophrenic, says, “With a painting, the presence is not what it means or what it looks like or what color it is or anything like that. The presence exists somewhere between the object in the painting and the person viewing it, and there’s a kind of energy field that goes back and forth. Some people pick it up and some people don’t.” When Sue puts shows together, she uses the right side of her brain; when I write about them, I use the left side of mine.

- - - - -

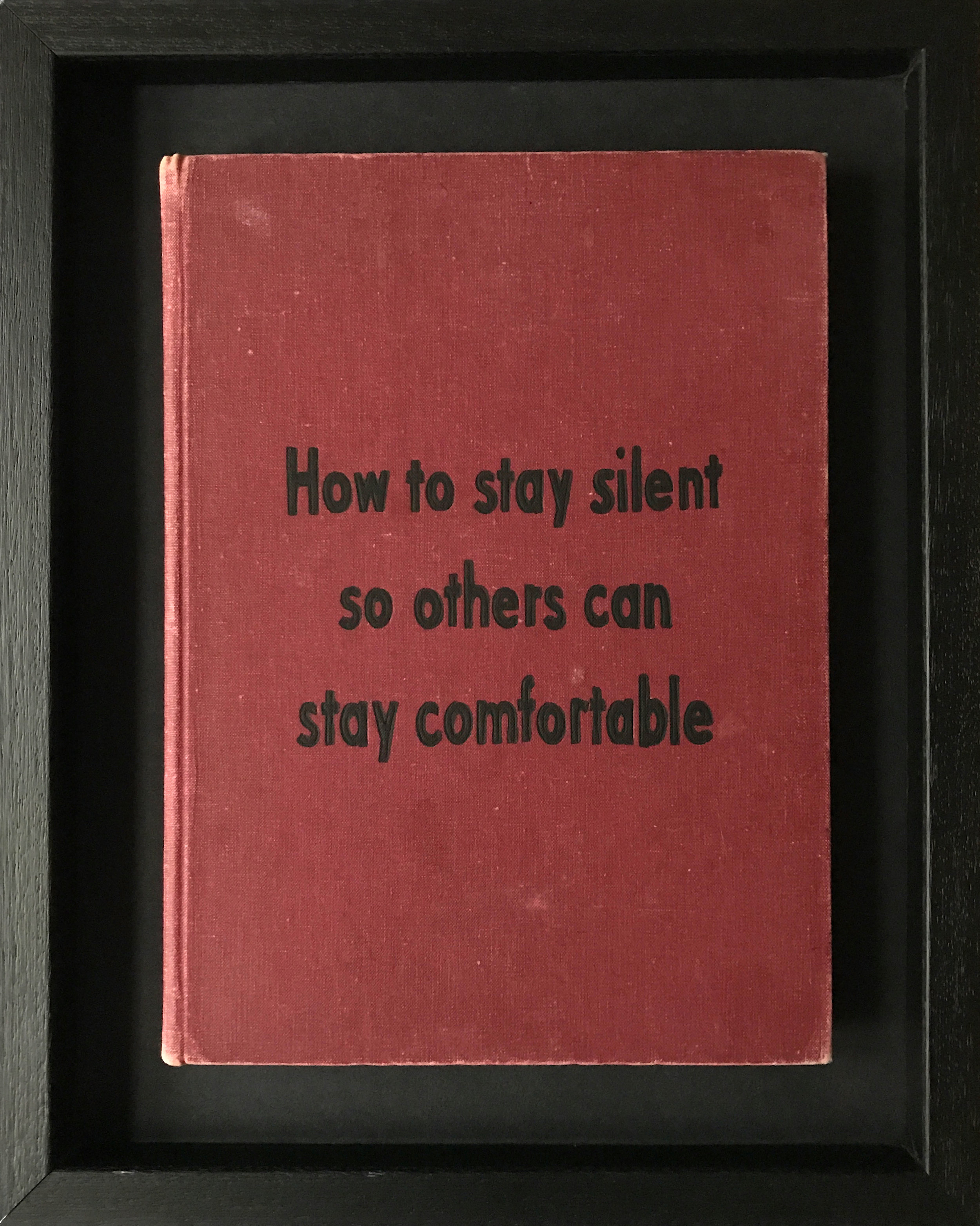

Johan Deckmann, First Editions, Waiting Room Installation View

Johan Deckmann is, by reputation, both an artist and a psychotherapist. His work, a series of book covers related to psychological truths, hangs in the waiting room of my psychiatric practice. Allan McCollum’s “Screengrabs with Reassuring Subtitles” was also mounted there. Sometimes there is a confluence of set and setting; at those moments life seems especially pregnant.

My favorite title was "How to feel the way you felt before you knew what you know now," but each title struck me as clinically true. Johan thinks like a shrink; he focuses on generating interpretive templates – tolerable truths – to help us organize, contextualize, and possibly master experience.

When I earlier wrote about McCollum’s “Screengrabs,” I said the project represented both our deepest need – for everything to be okay – and our most urgent fear, that it won’t. I’m a shrink, so I get to say this: the best way for things to be okay is to be loved. That’s what we want, even if we won’t admit it.

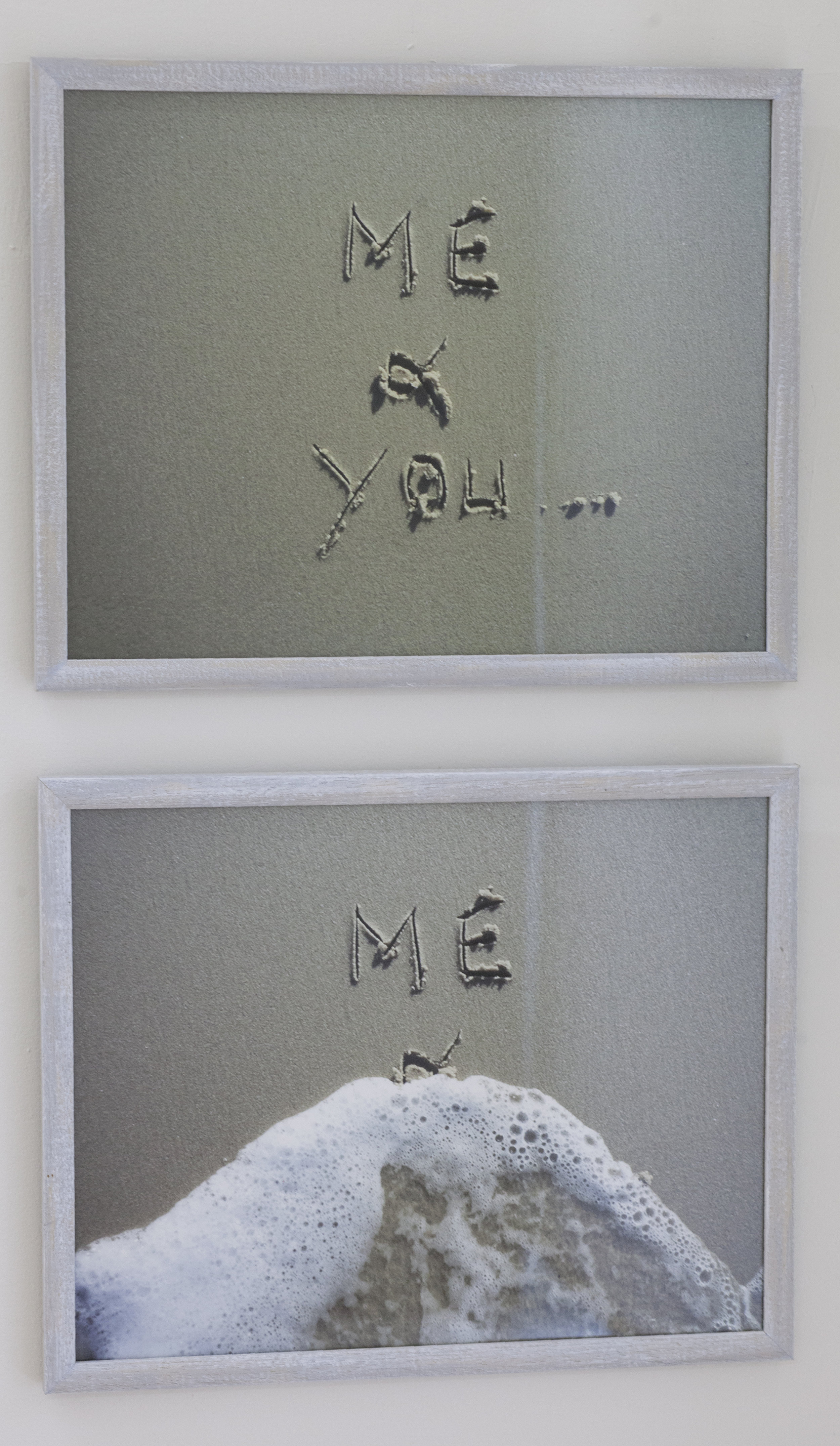

Brigitte Cornand, Me & You, Project Space Installation View

Brigitte Cornand’s photographs are about longing and the inevitability of loss. They are shocking, uncomfortably sentimental – no irony, no intellectual distance, just the experience of something valuable disappearing. They trigger an experience to which we have spent our lives generating a defensive response strategy. Sitting in the Project Space, surrounded by Brigitte’s photos, patiently taking it all in, what I thought is that although we live in a material world and everything is subject to entropy, this truth is endurable (given the right interpretive template).

Johan’s and Brigitte’s work is conceptual. It evokes recognition and reorganization at a macroscopic level. The other two shows are less cognitive; they don’t rely on language, on what we’ve already conceptualized. Robert Guillot’s work is composed of individual sculptural objects organized into moments of coherence. When you see the relationship of each thing to every other thing, you perceive an essence that resides within the relationship of these elements to each other. I kept thinking that if one thing changed, everything would change.

Robert Guillot, ...over and all about, Back Room Installation View

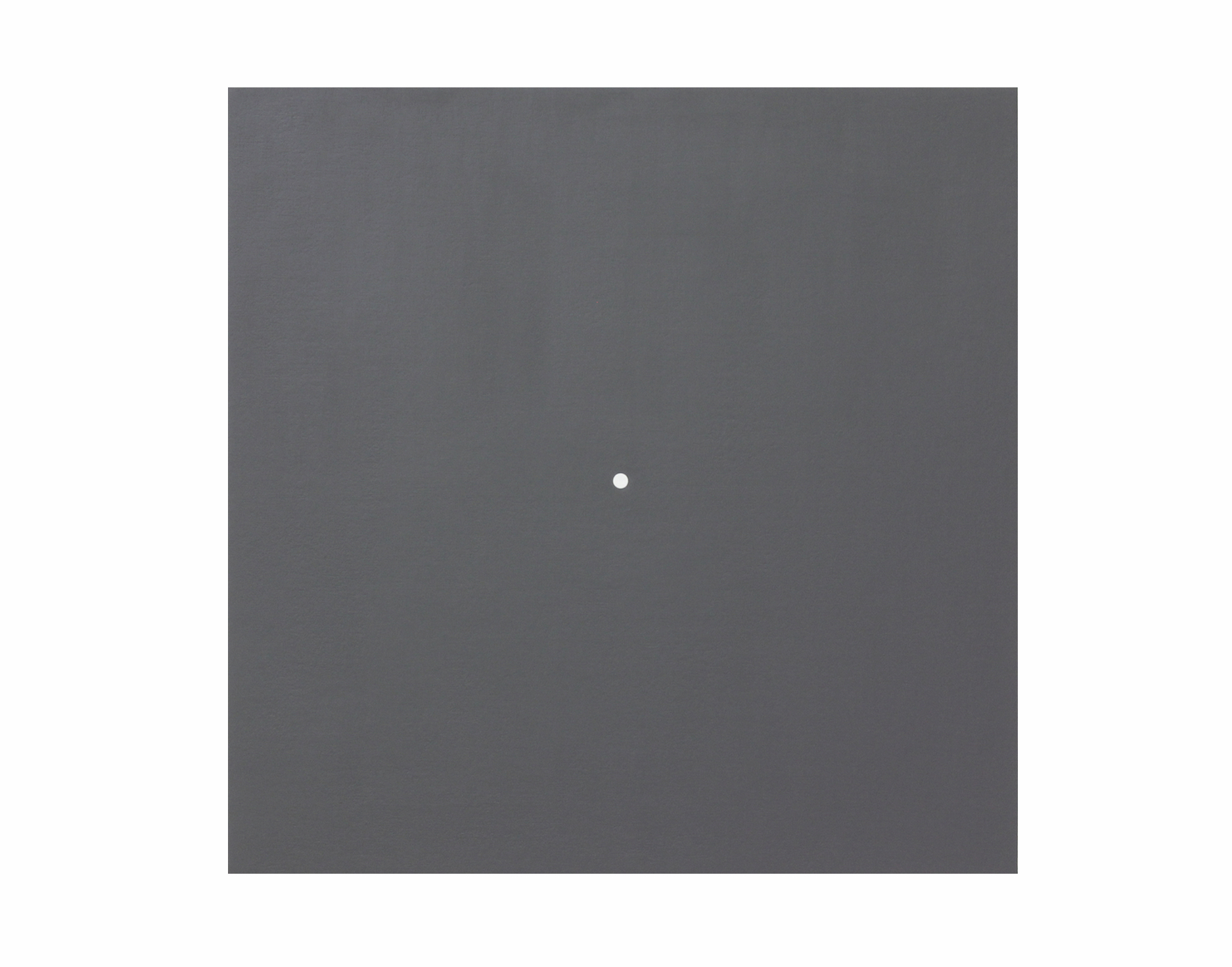

Guy Corriero’s paintings are also material manifestations of an imperceptible essence. His canvases look empty; in fact, they look scrubbed clean. There are hints of intention, though. You see that the surface has been worked over again and again. The point being, it's not easy to get to this invisible place, and once you're there, it still doesn't always seem comfortable.

Guy C. Corriero, Backward Thinking, Main Gallery Installation View

Preliminary Conclusions 7, Al Ravitz

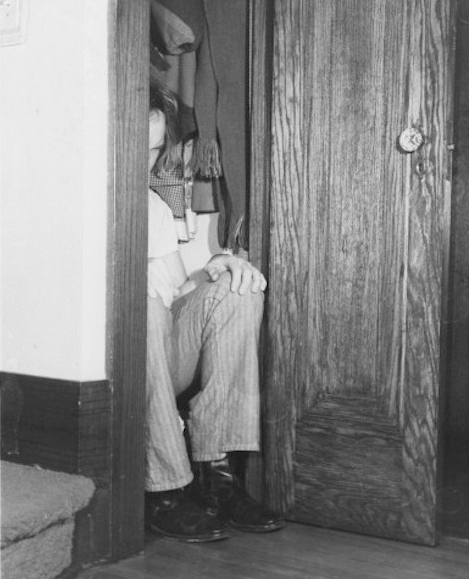

Double Cross: STEPHEN BEAL, Recent Paintings

FRED ESCHER - H-I-D-I-N-G

TOM HACKNEY - Open Ground

BARRY CANTER - Ceramic Sculptures

On view: September 8 - October 20, 2017

I first noticed Fred Escher's art in the late 70s, about the time Sue and I began collecting. Most of the work that we liked then no longer holds our interest, but I continued to think about Fred.

H-I-D-I-N-G is a set of photos from 1972, of Fred – hiding. At first, you have to look closely to find him. But like most work that relies on memory to enrich perception, the main image and its context is different at every engagement. It is a slow revelation that, as far as I can tell, has to do with encountering the same thing under different circumstances. In this series of photographs, Fred quietly inserts himself in different worlds. You get the sense from seeing all these pictures that there is another, invisible world that can only be experienced by seeing all the photos together, and then remembering what that was like.

Fred Escher, H-I-D-I-N-G, Waiting Room Installation View

The invisible world is an idea I keep coming back to. I wish I could define it better. It has to do with work that is about something other than simply the way it looks. Tom Hackney’s paintings are static representations of an extended period of time. He marks the time by hiding the canvas with paint according to a specific set of rules. The amount and distribution of paint on each canvas is determined by the moves of a Marcel Duchamp chess game – on a specific date, against a specific opponent. Tom paints a picture of that chess game. I can’t help but imagine the real activity the painting represents. It evokes and then sustains an interaction between perception and memory.

Tom Hackney, Open Ground, Project Space Installation View

Stephen Beal's paintings are hidden as well. Subtle manifestations of intention and accident, they are less predetermined than Tom’s chess games. As I see and remember Steve’s pictures, I’m continually reminded I can never remember everything I see. There’s always something I hadn’t noticed before. So many lines, so many borders, so many small systems interacting to create larger self-organizing systems, informed and energized by my serial looking and remembering.

Stephen Beal, Double Cross: Recent Paintings, Main Gallery Installation View

- - - - -

Fred, Tom, and Steve make pictures that require an investment of energy in the form of extended, slow attention. Barry Canter’s sculptures induce a different experience. They are material manifestations of an otherwise imperceptible essence, little ceramic sculptures that simply acknowledge the way things are. They evoke an infrequent but deeply familiar sensory experience. It’s relaxing. The essence remains hidden to the intellect, but you have access to the feeling.

Barry Canter, Ceramic Sculptures, Back Room Installation View

Preliminary Conclusions 6, Al Ravitz

NIMBUS: The Figures of Clara Mairs and Clem Haupers

curated by Annika Johnson

NATHAN RITTERPUSCH - Lustre

AMY E. SILVER - Please God, Just Get Me Out of This Hole!

On view: June 23 - August 4, 2017

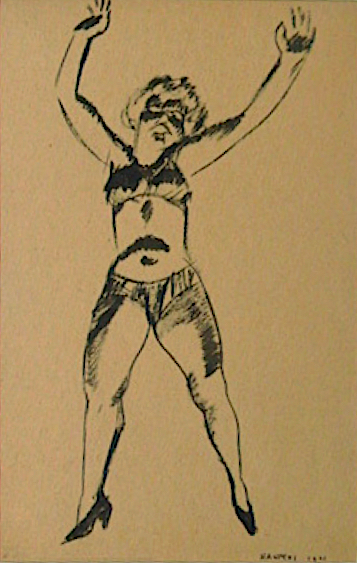

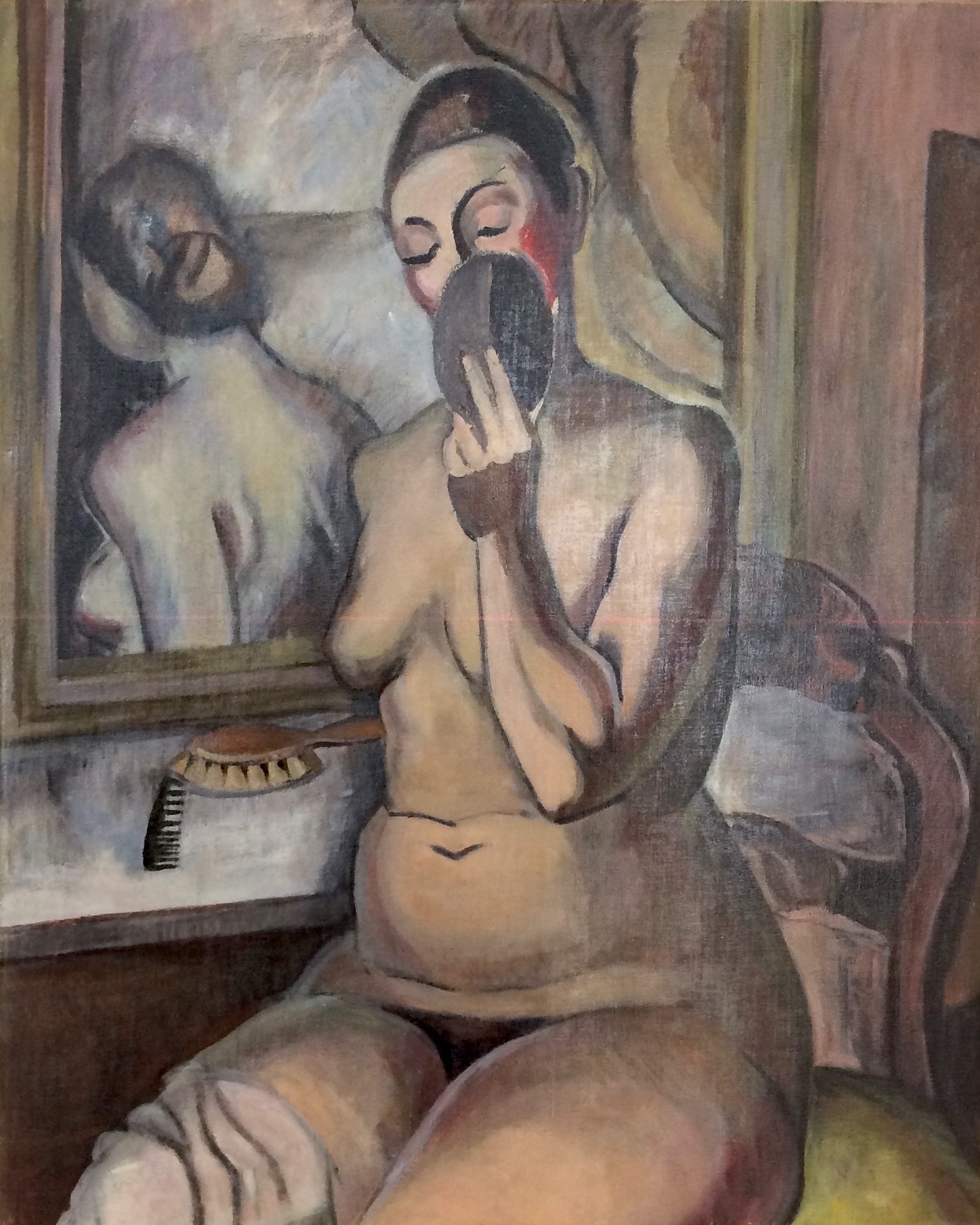

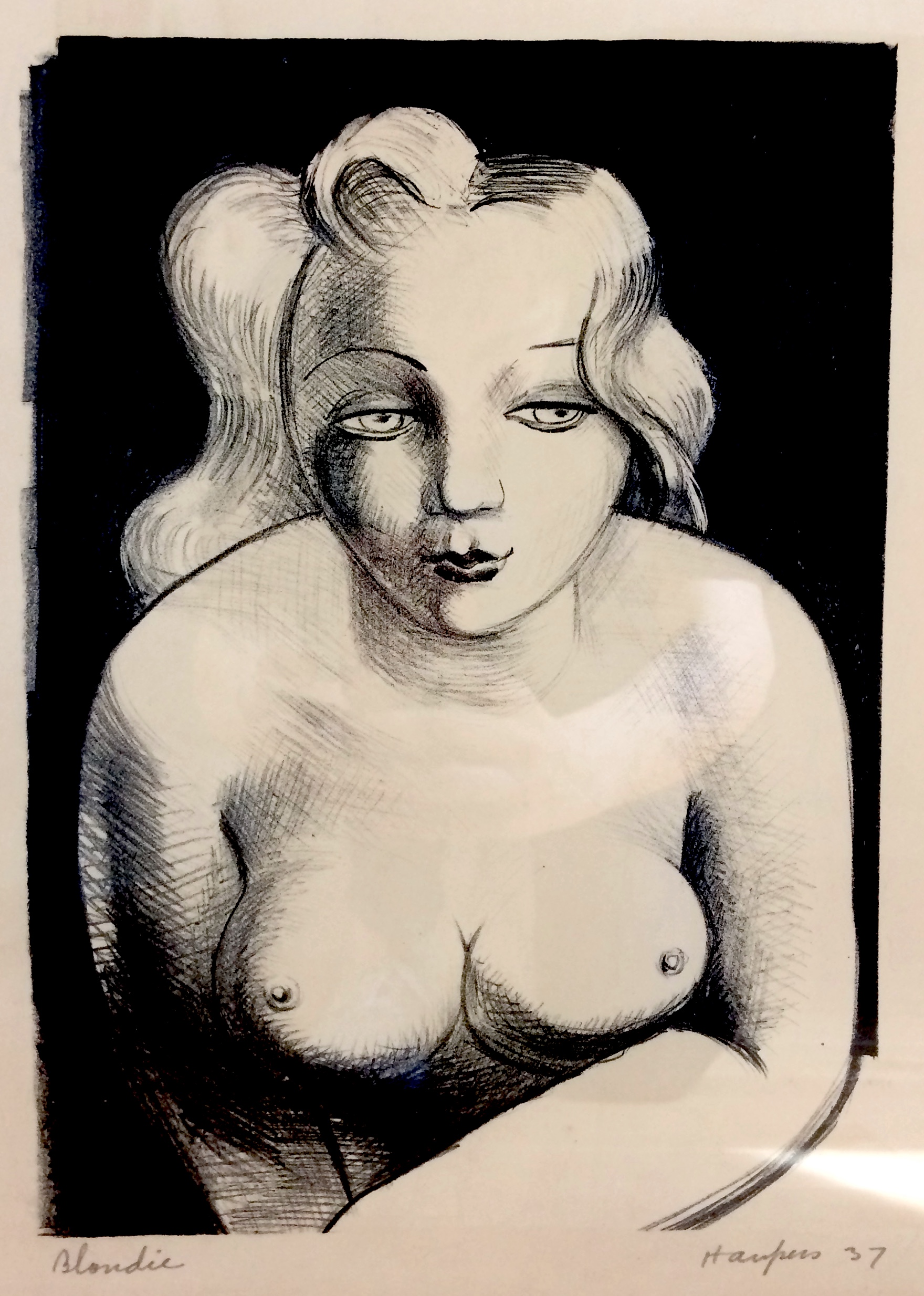

I came of age in the late 60s and early 70s. It was a highly sexual moment in time, the era of “free love.” Although there were occasional orgies, typically drug-fueled and not especially gratifying, most of the sex was conducted in private, in the context of an attempt at shared intimacy. In contrast, my wife and I were at the Brooklyn Bridge Park a few weeks ago. We saw a little girl who couldn't have been more than four or five years old. Her mother suggested a photograph. The girl pursed her lips, jutted out her hip, put her hand on it, and thrust out her chest, assuming the posture you’ve seen in hundreds of selfies. This lascivious pose was a kind of public performance of sexuality in the tradition of Paris Hilton and Kim Kardashian. The day after my initial observation, I saw another mother, another daughter, and exactly the same photographic enactment, this time in Central Park. The representation of sexuality these days is ubiquitous and purposeful. It’s a kind of stereotyped public performance of what really is a private experience; it’s a sexuality derived from pornography, even if the actors don’t realize it.

- - - - -

In the essay about the show before this one, I wrote that my particular engagement with art is motivated by a desire “to have a kind of nonverbal experience that is primarily neurological,” and that what I loved about Michael Voss's paintings was that they evoked a primitive, atavistic response by visibly unearthing things that exist only in the invisible world. This summer’s exhibition is sexy, even though it’s neither pornographic nor ”transgressive.” It’s focused on bodies, and on interpersonal acts contemplated and/or consummated. It generates, for me, the desired neurological, subcortical, non-linguistic, “just a feeling”-type response. This isn’t surprising, since from an evolutionary standpoint, nothing – not even aggression – is more atavistic than sex. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P53mWKRWaao, and if you’re still interested, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rvqedkn3mVY)

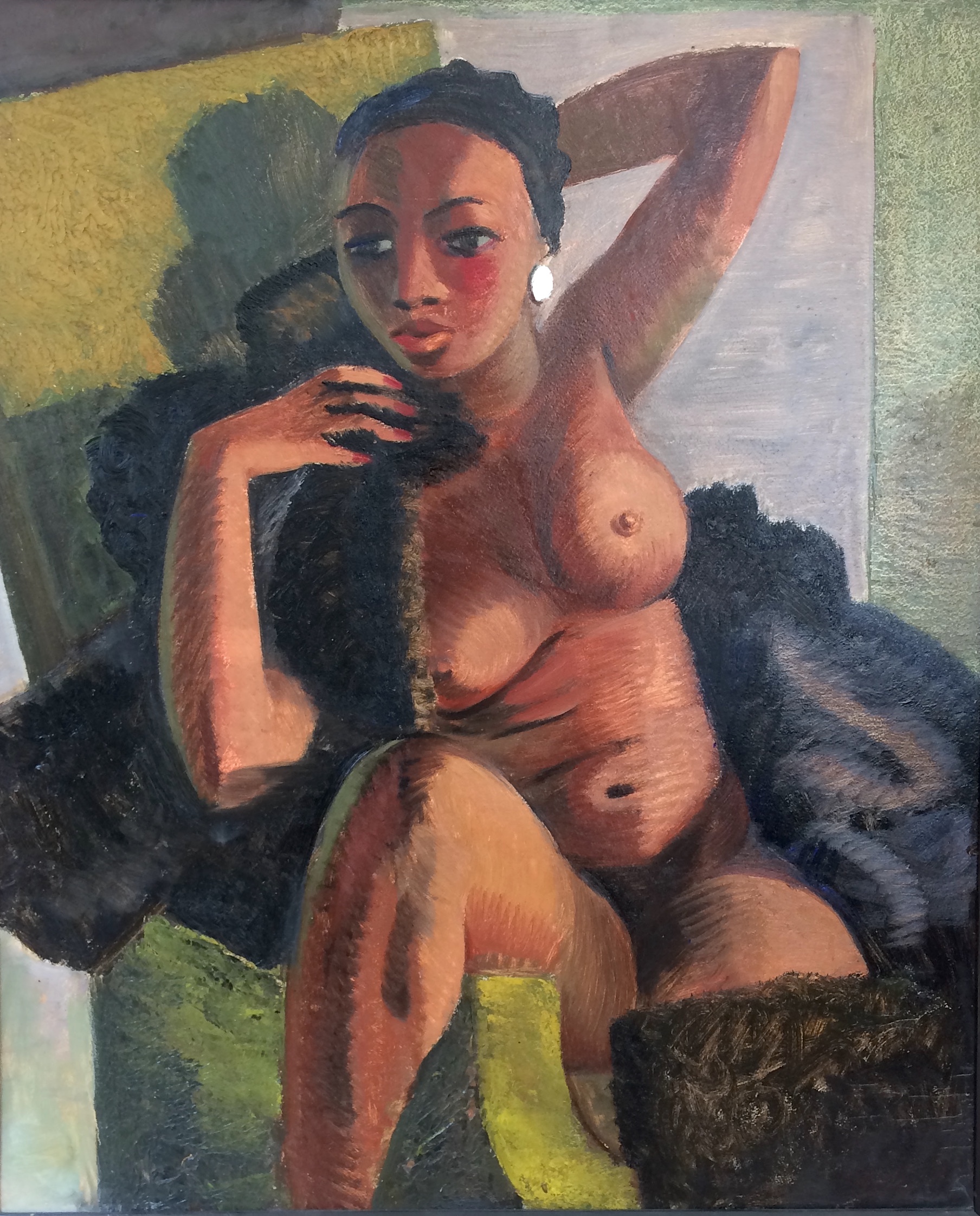

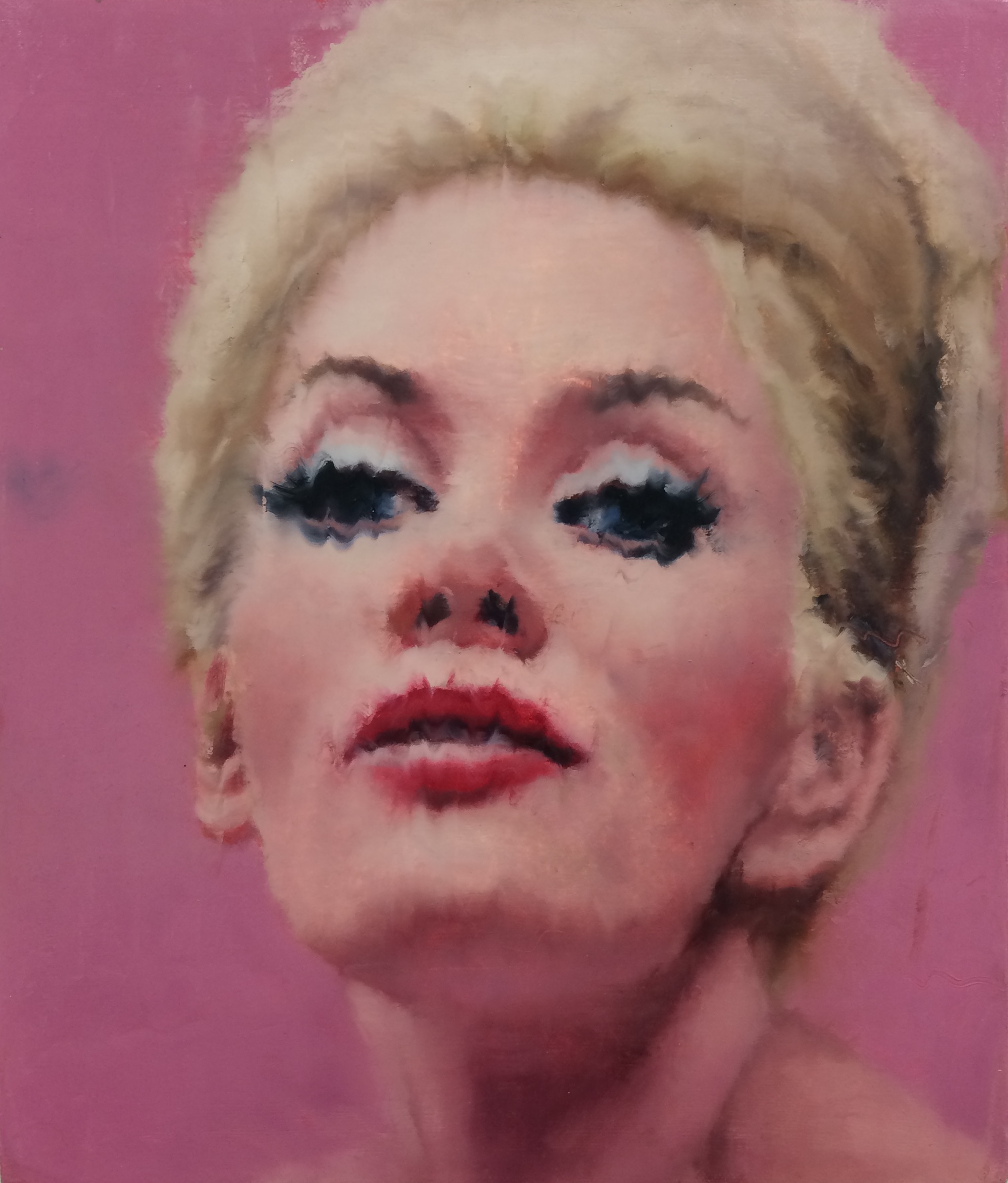

Nimbus: The Figures of Clara Mairs and Clem Haupers, Main Gallery & Project Space Installation View

As I’ve lived with these pictures over the last couple months, however, I’ve also had a neocortical, cognitive, language based response to them, uniquely predicated on my personal and professional experience. I began by thinking about the difference between the older work (Mairs and Haupers) and the more contemporary (Ritterpusch and Silver), and then about the cultural construction of sexual experience and the difference between public and private sexuality (see above), and then – good psychiatrist that I am – about the public and private experience of intimacy.

The older work is self-conscious, but only accidentally. Through formal means, it addresses questions of representation – of material, light, and space. Mairs reminds me of Morandi, in the way she flattens the pictorial field; Haupers, in contrast, creates volume. But both artists focus on the body. Their choice of subject matter and representational strategies suggest something deep and emotionally true, but the representation of psychological truth was likely not the artists’ primary motivation.

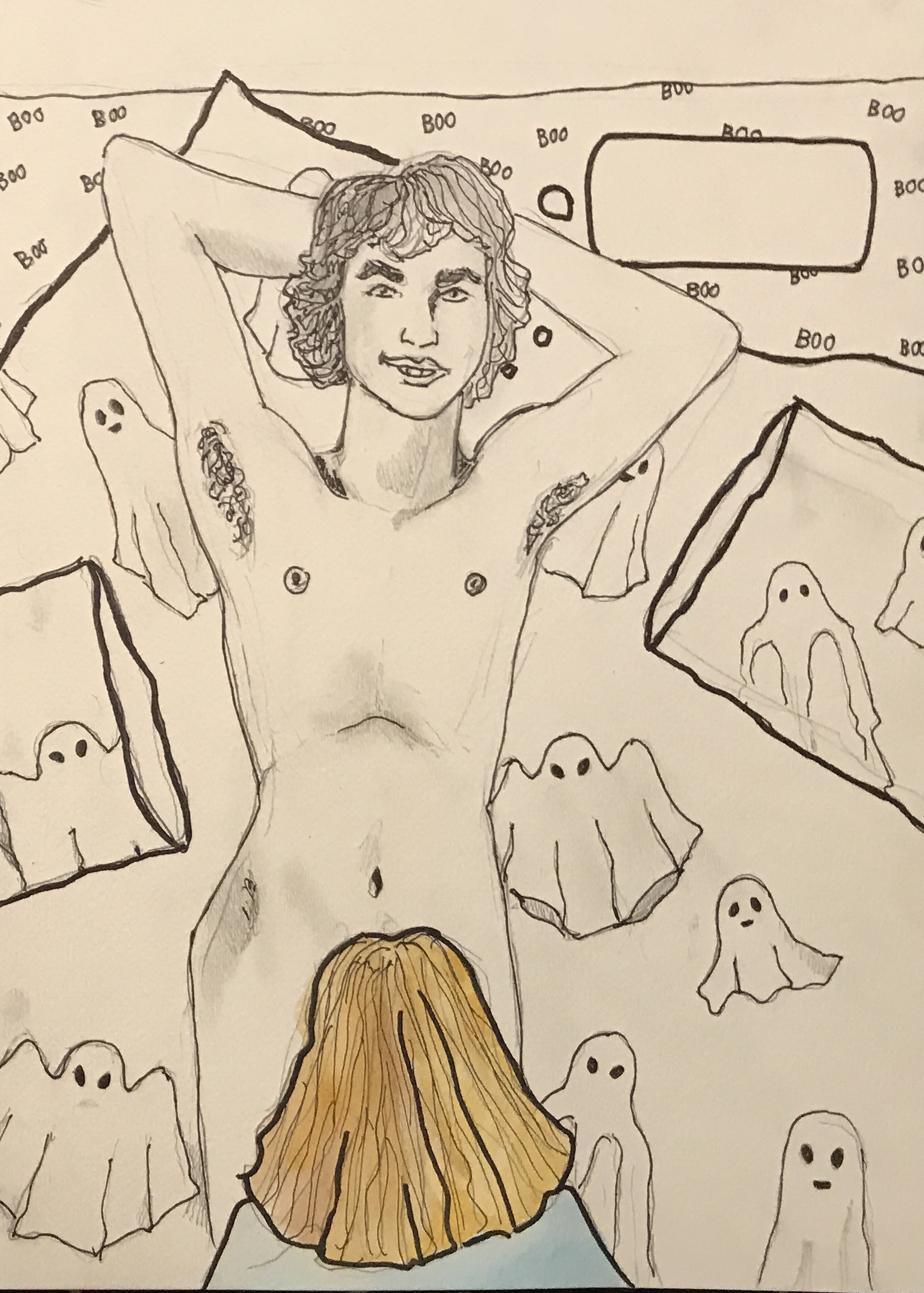

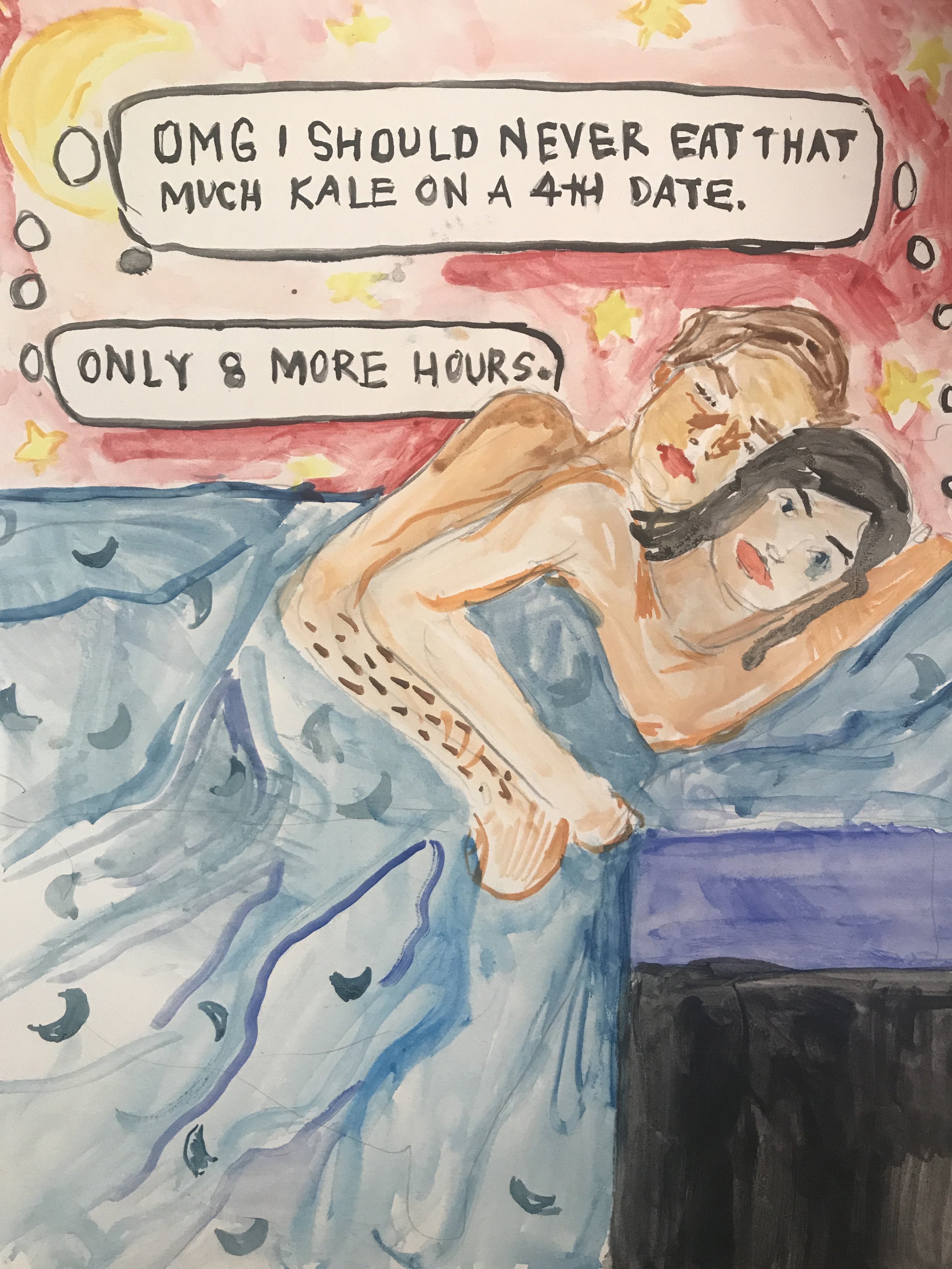

The newer work, on the other hand, is more overtly psychological. The formal devices it employs are in the service of its psychological message. It is purposely, publicly, conceptually self-conscious. Ritterpusch fantasizes sexuality, you see his mind working; while Silver contemplates sexual behavior and its emotional aftermath.

Nathan Ritterpusch: Old Enough to Be My Mother #9, 2017; Head #15, 2017; Old Enough to Be My Mother #89, 2017.

Amy E. Silver: Snore Less, 2017; Boo, 2017; The Long Night, 2017.

Preliminary Conclusions 5, Al Ravitz

MICHAEL VOSS - Paintings With Names and Related Drawings

TRACY GRAYSON - Waiting Room

DANIEL WENK - Recent Tapings

SEAN SULLIVAN - WEST/END/BLUES

On view: April 28 - June 9, 2017

In my life as a clinical and forensic psychiatrist I interact with complex interpersonal systems. I’m interested in phenomena called “person-environment transactions.” During these events, the system (the person, the relationship) endeavors to maintain stability via a number of perceptual/interpretive/behavioral maneuvers. We develop certain predictive templates and then – to grossly overgeneralize – do what we can to make sure they come true. We associate with people who make us comfortable and reinforce our predispositions; we interpret our experiences in a (rigidly) consistent way and tend to ignore data that doesn’t support what we already believe; and if we don't get the response we expect from others, we engage in behavior that evokes our self-fulfilling prophecies.

When we look at things we also utilize predictive templates. We encounter a visual stimulus, associate it with other stimuli, and identify it as an example of a genus (e.g. zombie formalism) that either appeals to us or doesn’t. The perceptual experience, then, is complicated by memory, associations, and consequent expectations. My approach to being with art represents a practiced attempt to free myself of those perceptual and cognitive predispositions. The most appealing work evokes a reorganization of the templates that I use to interact with the world. I’m interested, as I’ve mentioned before, in the invisible aspects of my perceptual experience.

So now that you're entirely confused, let's talk about the work in the last show. I never know how to start these things. I look for organizing principles, but I recognize there’s something artificial about that. Nevertheless, it helps me to organize my thinking.

Tracy Grayson, Waiting Room exhibition, Installation View

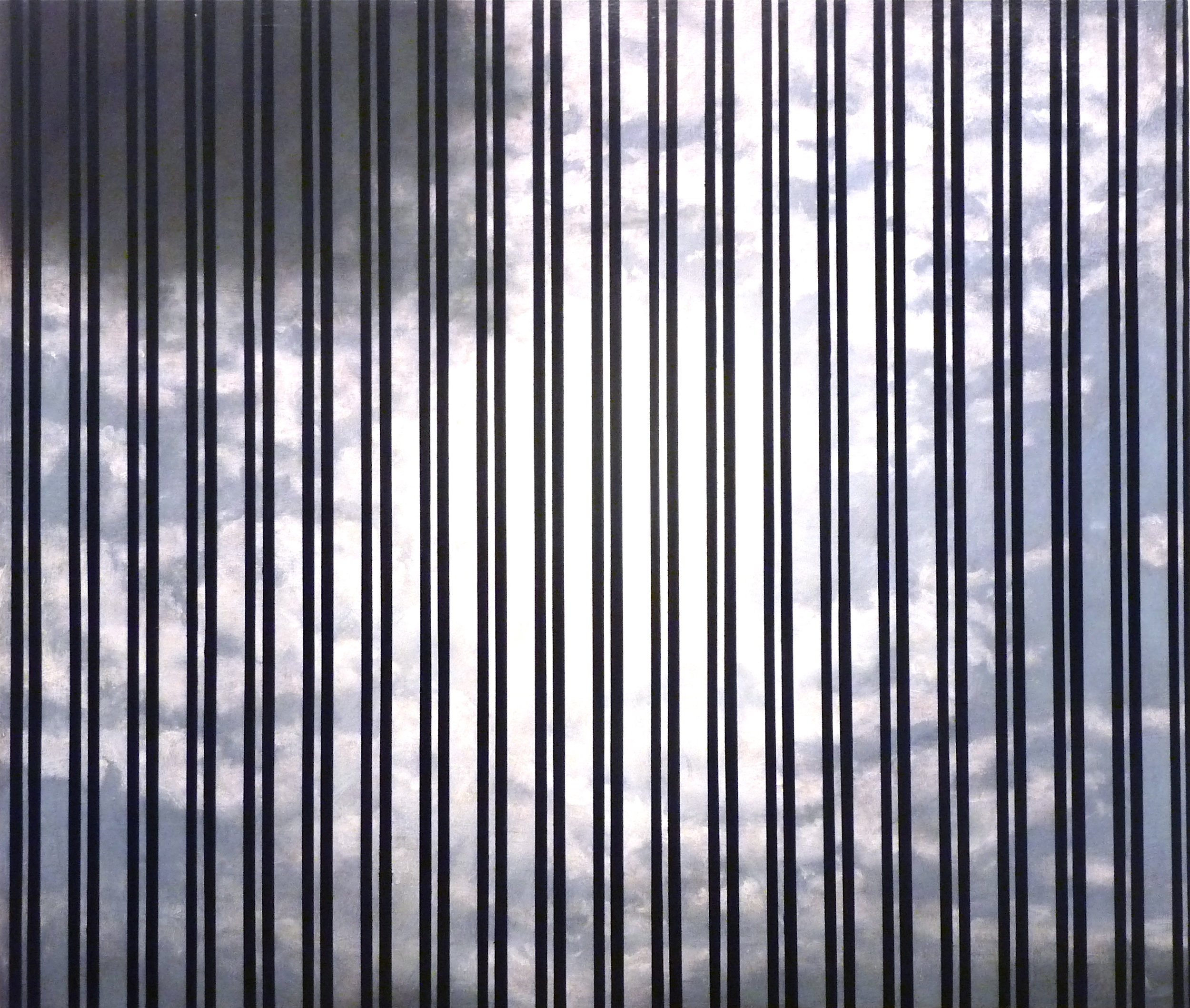

First, Tracy Grayson's paintings: what initially struck me about them was the way he painted the sun. It’s such a strong effect. The sun literally shines from below the surface. It was interesting (to me as a layperson) how he could use paint to create a light source. Eventually I began to see the rest of his work as an analysis of the way we perceive things. How could he divide the space while continuing to evoke representation? What perceptual assumptions do we make when we look at things?

As I’ve mentioned ad nauseum, there is something to be said for living with art rather than just looking at it. We can chip away at optical predispositions; we can allow memory and experience to influence perception; we can build new templates to manage our experience of the world from a perceptual standpoint. We can continue to modify the invisible world we inhabit.

Daniel Wenk, Recent Tapings, Project Space Installation View

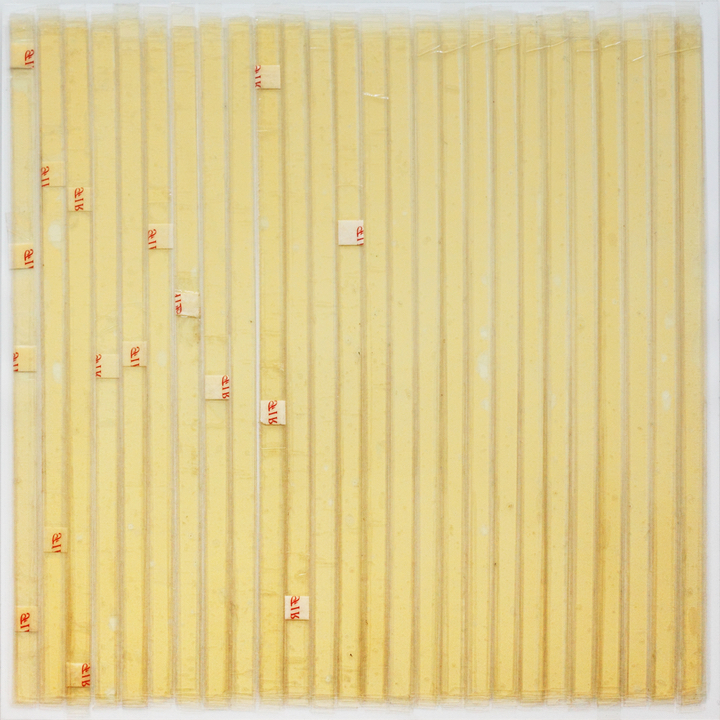

Daniel Wenk has been doing the same thing for the last 30 years. He covers things with transparent tape. There is something very optical about the end result. It's difficult to attribute "meaning" to these objects. They are strictly experiential. He converts opacity to translucency. He generates an interaction between material and light by compulsively utilizing this ubiquitous material. Even though he does the same thing over and over, each instance evokes a different effect. It raises a kind of question: does the repetition of the same thing, in an attempt to engender a certain experience, engender yet another? Last month I referred to Peter Dreher’s glasses. They come to mind again.

Sean Sullivan, WEST/END/BLUES, Back Room Installation View

Sean Sullivan also creates variations on a theme. Even though the works don’t look alike, they all seem to be about the same thing – a relatively straightforward representation of some aspect of the world to which we typically don’t pay attention. The titles often hint at what he is up to: getting us to re-look at something we see every day. The fact that his work is all on reused material adds a concretely invisible aspect to it. You know there's something on the other side, but you can't see it. You know the object has a history, but you don't know what it is.

Michael Voss, Paintings With Names and Related Drawings, Main Gallery Installation View

Finally, Michael Voss's paintings. When I begin writing these preliminary conclusions, I never know exactly what I’m going to say. Writing this little essay, I've noticed that I’m motivated to have a kind of nonverbal experience that is primarily neurological – with a deep history, evolutionary as well as personal. Michael Voss's beautiful, simple paintings evoke an atavistic response. The things he paints are like physical objects he has been trying to uncover. But once he gets to where he wants to be, and the thing is exposed, it turns out to be nothing I’ve ever seen before. That's what I want. Just that experience. Seeing something I've never seen before.

Preliminary Conclusions 4, Al Ravitz

RICHARD VAN DER AA - pictures of paintings

JOSHUA HUYSER - Shivelight

SKY GLABUSH - Surfacing

NOEL MORICAL - Friendly Ghosts

On view: March 3 - April 14, 2017

I've been living with the show we just took down for a couple of months now. Sue usually makes the curatorial choices, and although I knew this one hung together, the left side of my brain couldn't quite put things into verbal perspective. Although I can respond to things affectively without the need for language, I like to put things into words – even though it’s usually quite painful:

There is nothing spiritual about any of the work. Rather it’s about non-narrative materiality, which is the kind that appeals to me the most. Non-narrative content is usually what I’m looking for; otherwise I’d rather read a book or see a movie.

Richard Van Der Aa, pictures of paintings, Main Gallery Installation view

I’ll begin with the Richard van der Aa paintings. They look like pictures of defined areas of emptiness, but they are actually densely material representations of a single painting (under different conditions, I imagine). So they are densely representative, like Peter Dreher glass paintings.

Joshua Huyser, Shivelight, Waiting Room Installation View

Joshua Huyser’s watercolors look as if he is painting the opposite of emptiness. But, he's putting things – mostly empty vessels – into an empty field, drawing out the distinction between something and nothing. So, in contrast to van der Aa, Josh is really painting emptiness, an emptiness that’s highlighted by the intrusion of a thing in an empty field.

The other two artists more sculptural. Rather than creating representations of things in emptiness, they create real things in real empty space.

SKY GLABUSH, Surfacing, Project Space Installation View

Sky Glabush’s painted weavings look two-dimensional, but they have texture. This is not a representation of a material thing. It is an actual material thing that is imbued. I'm not quite ready to say what it’s imbued with. I haven't thought about it enough.

NOEL MORICAL, Friendly Ghosts, Back Room Installation View

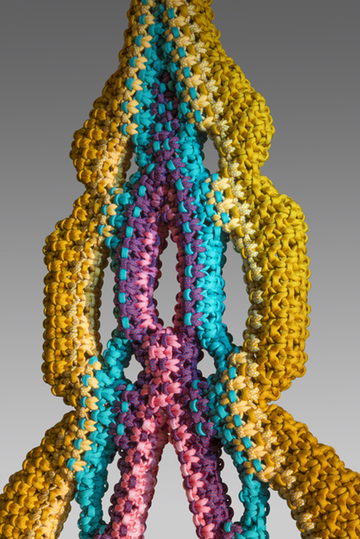

Finally, there are Noel Morical’s sculptures. When I sit with them, I’m reminded of Ruth Asawa – only psychedelic, mind expanding. Noel’s work is imbued with tactility and color, and it is suggestive. Almost like a weird experiment to investigate the way material objects with certain qualities can inhabit and transform space. And the shapes of these things allow Noel to work intensively with color in a space impossible to capture with painting.

Both Sue and I love grabbing these sculptures. Their tactility creates a certain kind of comfort. It feels really good to squeeze them. That is an amazing quality for an object to have, squeezability. That's what I mean about psychedelic. It's mind bending.

Preliminary Conclusions 3, Al Ravitz

JOHN MENDELSOHN - Dream Garden

ANNA SHTEYNSHLEYGER - 26 Court

JOHN PHELAN - Seats and Chairs

On view: January 6 - February 18, 2016

I've been a psychiatrist for almost 40 years. I do a lot of different things, but the thing I do the most is work with divorcing families, either as a court ordered custody evaluator, a parent coordinator (someone who helps divorced couples make decisions about their children), or a couples and/or individual psychotherapist. In this capacity, I spend my days listening, talking, and writing reports.

I also collect art – again for about 40 years. As far as I'm concerned, the psychiatry and the art are not really connected. In fact, when I hear people getting all psychological about art and artist, I get bored and sleepy. I want to activate some part of my nervous system that cannot be linguistically characterized. I want to feel something rather than think something. This is what I wrote about this previously: “There is a real but invisible world that each of us uniquely inhabits. Its characteristics are based mostly on chance – genetic endowment; the physical and social circumstances of daily life; history, both personal and cultural; and of course, good or bad luck. When we encounter something that allows us to make contact with that invisible world, the result is a psycho-aesthetic experience.”

ANNA SHTEYNSHLEYGER, 26 Court, Waiting Room Installation View

Anna's Shteynshleyger’s show, “26 Court,” represents a challenge to my non-verbal bias. I very much like the formal aspects of the exhibit – a bunch of essentially monochrome photos and a few crazy monochrome sculptures. But the work also clearly relates to her experience of divorce, and this is a subject with which I have a great deal of professional familiarity. I see divorcing people almost every day. I listen to them and try to understand them. If I’m doing treatment, I try to help them.

Anna's work clearly derives from the biological, psychological, historical, legal, and socioeconomic complexity of her divorce, but I don’t want to try to figure out what these photographs and sculptures mean, or what they say about the artist. That would be just like going to work – and besides, there is more to the work than the divorce. I want let these things wash over me. She’s taken her experience, abstracted it, and then created a series of objects inhabited by that abstracted experience. It gives me a "nothing is free" feeling, but it might give you something entirely different.

JOHN PHELAN, Seats and Chairs, Project Space Installation View

John Phelan’s show, “Seats and Chairs,” just boils down existence into its very simple essence. During my late adolescence I “discovered,” through a variety of activities, that everything is connected to everything else. Phelan's room compresses this “everything is everything” concept into a tight but very familiar loop – asses serve a variety of functions. How lovely. How deep.

JOHN MENDELSOHN, Dream Garden, Main Gallery Installation View

Finally, John Mendelssohn's paintings really do resist any verbal narrative. Whereas the other two exhibits are conceptual, Mendelsohn's is purely visual – just color, surface, and material. It's an investigation without words. It evokes a psycho-aesthetic response, especially at certain times of the day, that is exactly what I’m looking for.

Preliminary Conclusions 2, Al Ravitz

GWENN THOMAS - Standard Candles

LAEL MARSHALL - Waiting Room

MICHELE ALPERN - Project Space

On view: November 4 - December 17, 2016

When I wrote about Anne Thompson’s Color-Word Value Index, I said her project resonated with something that stubbornly resists definition, “a real but invisible world that each of us uniquely inhabits … based mostly on chance – genetic endowment; the physical and social circumstances of daily life; history, both personal and cultural; and of course, good or bad luck.” When I wrote about the next show, I thought about the intersection between memory and perception.

MICHELLE ALPERN, Project Space Installation View

The Michelle Alpern drawings in our Project Space reside within a very specific environment – mounted in books on a table, lit with specific table lamps, you have to wear gloves to turn the pages. It’s hard work. The images are tiny – tiny – so small you don't want to bother to look at them because you assume there will be nothing there to engage your interest. It just looks indecipherable. You have to force yourself to sit and open (or empty) your mind, so you can inhabit the invisible world. After some effort the images expand until you can see something, but what you see turns out to be indecipherable, a language without symbols or narrative content. It’s an itch you can’t scratch, so you just have to get used to it. The process is liberating; it frees you to see things in an entirely new light.

LAEL MARSHALL, Waiting Room Installation View

Lael Marshall utilizes recognizable domestic materials to create abstract shapes. She suggests a language composed of familiar referents, but she dissects out the meaning. To see her objects you have to let go of your assumptions about both domesticity and abstraction. There is no specific meaning, just a suggestion that there is a wide variety of experience.

GWENN THOMAS, Standard Candles, Main Gallery Installation View

Gwenn Thomas’s Standard Candles is in the main gallery. Her photograph and wall paintings challenge our physical perception of the world. Her photographs of windows evoke a feeling of depth, when in fact they are super-flat. Her wall paintings under translucent Plexiglas look incredibly flat when in fact they enclose and therefore influence a series of empty spaces.

It's good to question the nature of the universe. Blah blah blah …

Preliminary Conclusions 1, Al Ravitz

ANDY SPENCE - Friends and Places

ALLAN McCOLLUM - Screengrabs with Reassuring Subtitles

MATTHEW FEYLD - One, Two, Three

On view: September 9 - October 21, 2016

The nice thing about running a space that shows art is that I get to live with the work. This “living with” evokes certain experiences. I form memories of those experiences. Each time I see the work, my perception is influenced by my memory. This, in case you haven't noticed, is an argument for living with art rather than just looking at it, which is an argument for collecting.

Anyway, here is a summary of my experience of living with our last show: I first saw Andy Spence's work in a catalog from 1992. He was an artist who, in some way or another, seemed to create abstract representations of things that existed in the material world – e.g. the metal siding of a trailer, or the shape of the seat of an Eames chair.

Allan McCollum is an artist whose work I’ve followed for many years. He idiosyncratically abstracts the essence of things we classify as art. The experience of his work is disconcerting – it challenges all sorts of assumptions. He said he might have an interest in doing a sort of site-specific project for the waiting room of my psychiatric office.

In our small project space we decided to do a show of paintings by Matthew Feyld, a young artist from Montreal who Sue met on Instagram years ago, and whose work we collect and exhibit.

The shows were hung. Sue and I were satisfied with the way they looked. Six weeks later I'm thinking about the work as it comes down.

First, Andy Spence: His Friend Paintings are self-portraits that are both anonymous and distinct. He repetitively paints and sands each one, until the canvas ground becomes entirely invisible. What is left is an image of a complex psychological construct, made entirely of paint, and made corporeal through the use of a collaged canvas shape. But the corporeality is generic, without specific narrative meaning. All the detail is nonverbal – surface, color, depth, shape, size.

ANDY SPENCE, Friends and Places, Main Gallery Installation View

Next, Allan McCollum: In the past he has always abstracted ideas (I think) but the current project, “Screengrabs with Reassuring Subtitles,” abstracts an affective experience. It represents, in180 iterations, both our deepest need – for everything to be okay – and our most urgent fear, that things won't be.

ALLAN McCOLLUM, Screengrabs with Reassuring Subtitles, Waiting Room Installation View

Finally, Matthew Feyld: His work is more experiential than conceptual. While the show was up I periodically sat in the chair in the middle of the room with the three paintings, so I could be with them. I was struck with how the light traveled through the layers of paint, evoking an altered experience every time I sat with these simple white dots. The result was that they always looked a little different than when I last viewed them, which gets back to this whole idea of living with art rather than looking at it.

MATTHEW FEYLD, One, Two, Three, Project Space Installation View

![Beverly Rautenberg, [My] FAVORITES, Project Space Installation View](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/53c9433de4b029ce6ccd263a/1522030087559-2SY10W4RCWU5IV9GSEAP/image-asset.jpeg)